|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

apse and built the existing sanctuary over its east end. This has a typical Norman quadripartite cross-vault but it is quite plain: there is none of the dog-tooth moulding of some other Norman vaults and there is no decorated centre boss. The ribs are formed of double roll mouldings. The sanctuary arch was another matter. Here we do have dog-tooth moulding and of an unusual kind: the pattern faces outwards toward the nave rather downwards towards the floor. We were told that this is one of only two such in the country. Both the arch and the cross-vault spring from clusters of three short piers which rest on projecting masonry courses on either side of the arch. There are corresponding single short piers at the eastern corners of the sanctuary. This is an unusual arrangement. The effect is, as the Church Guide nicely describes it, of “forming a stone canopy over the holy of holies”. The rest of the apse became part of the existing choir, thus the church became a three-celled one, although both choir and sanctuary are very short. A Norman window survives on the north wall of the sanctuary. It cannot have been very long before the aisles were added and church extended westwards because the rest of the church is decidedly Early English in character. Pevsner puts the North aisle at about 1200, very early in the EE period. A little later the South aisle was built and the nave remodelled with a third bay extending the nave westwards. That seems to have been about it until as recently as the 1840s when the there was further extension westwards with a fourth bay being added to the nave. The windows in the North aisle were replaced in 1839 in a pseudo Early English style that did nothing to damage the pleasing appearance of this church. There has never been a tower here. There are some other curiosities here. Over each of the two pairs of Early English windows in the south side of sanctuary there is a little head set into a recess above. Pevsner describes it as “minimal form of plate tracery”! I haven’t seen anything like this before. In fact, this kind of adornment is quite unusual in the EE period so perhaps it was done later? Beneath the Norman window in the sanctuary is the head of a stone cross that was found beneath the vestry floor. It is now believed to be an Anglo-Saxon “preaching cross” around which people would gather when churches were few. The Celtic form of Christianity as evinced by St Aidan was much less hung up on the availability of sacred buildings than the Roman version championed by St Wilfred. Escomb in County Durham has a very different example behind its altar of what also might have been a preaching cross. There are two decorative capitals on the North arcade. Such chunky capitals would be unusual in an Early English arcade and the decorations do not look at all late Norman. The church believes that they were recovered from a disused Roman building. All in all, there is a lot to see here in a church that seems to be in the shadow of other churches nearby with Anglo-Saxon provenance. Quite why this should be so is not clear to me. Heddon is both attractive and interesting and few churches are more welcoming to visitors. If you are in the area on the Trail of the Anglo-Saxon please don’t miss Heddon-on-the-Wall off your itinerary. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||

|

|||

|

The two rather surprising capitals of the north aisle. That on the left certainly does not look Norman and the church firmly believes it to be Roman.. That on the right is more Norman-looking with its water leaf design at the corners. The foliage is reminiscent of the Roman capital so perhaps the builders consciously mimicked it. |

|

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

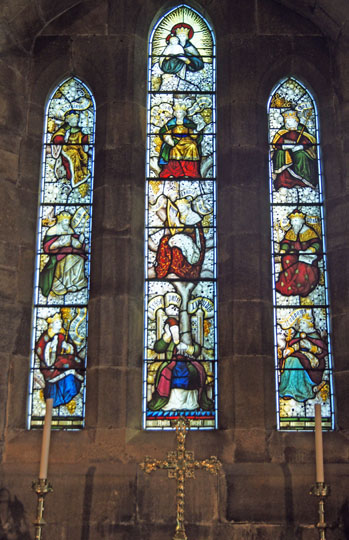

Left: The Norman sanctuary seen from the choir. Note the elegant triple clusters of half-pillars supporting the arch and the vault. Centre: Detail of the unusual forward-facing Norman zig-zag moulding. Right: The glass in the east window is a Jesse Window (showing Christ’s family tree from Jesse onwards) made by Charles Kempe. Unusually, it does not have Kempe’s trademark “wheatsheaf” symbol. Thus, it is believed to be a very early example of his work. The window itself is a typical triple lancet Early English configuration, albeit restored in the c19. |

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

In a church where you would be hard-pressed to identify many of the modifications that have occurred over the centuries such has been the care taken, the awful bodging of what would originally have been the semi-circular sanctuary arch is a surprise and disappointment. The Norman vault, however, has a lovely simplicity and cleanness of form. |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Left: One of the beautifully-executed half pillars supporting the cross vault at the east end of the sanctuary. Centre: The only remaining Norman window in the north side of the sanctuary. Right: The Anglo-Saxon doorway in the south side of the choir. Don’t be deceived by the modern lintel - look at the arched top above it. |

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

Left: The Preaching Cross displayed below the Norman window. Centre: The incorporation of tomb slabs into the fabric of churches in not particularly uncommon, but it is rather commonplace in this part of the country. This one set below a window in the choir is a fine one, however, clearly belonging to a knight of some substance. Right: The simple Anglo-Saxon font. Compare it with the much more substantial immersion font at Escomb. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

Left: Anglo-Saxon long-and-short-work at the quoin of nave and choir. Note the Anglo-Saxon doorway to the right. Note also just above the window the faintest outline of the original roofline. Centre: The blocked Anglo-Saxon doorway through to the choir. Right: Those who have read a lot of these pages will know I am no great fan of stained glass but Heddon’s windows are very nice indeed and were given by Sir James Knott in memory of his two sons killed in World War I. In this pair of windows we have on the right an exceedingly rare occurrence of Joan of Arc in an English church, complete with armour and the fleurs-de-lys crest of France. To her left is St George, and the Maid of Orleans must be highly flattered to be represented as having been as tall as he was! |

|

|

|

||||

|

||||||

|

Left: One of the Early English chancel windows with a head inset above it. Centre: Close ups of the two badly weathered heads Right: The east end. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 1 - The Normans and Northumberland Churches |

|

In most churches south of Northumberland and Durham (and I knowingly make a massive generalisation here) the familiar pattern is a largely decorated or perpendicular exterior and some Norman fragments: part of the tower and, if you are lucky, one or both aisle arcades. In this part of the world, however, the familiar pattern is an Early English exterior with Anglo-Saxon fragments The most obvious reason for this discrepancy is that until the Norman arrived there were very few stone churches. The wooden ones of the Anglo-Saxon era were replaced by Norman structures that were expanded during the C14 and C15. The English kingdom of Northumbria, however, was relatively rich in Anglo-Saxon stone churches so there was no compelling reason for a rebuilding program. The relatively small Anglo-Saxon structures, however, would have been judged inadequate rather earlier than their later Norman counterparts and would have required expansion sooner - in the Early English period. Another element might well have been the general resistance in the North of England to Normans. There was great savagery on both sides before the north was subdued but even then the Norman nobles might have been more preoccupied with military than with ecclesiastical matters. I might add that the Normans, of course, undertook the massive job of building Durham Cathedral and of reviving several moribund monasteries in the area, including Hexham Priory, so it could well be that there were no masonic resources to spare. Well, those my own theories and if you are a professional historian feel free to tell me I am talking rubbish! Whatever the reasons, in Northumberland Diana and I got very used to arriving at a church to be confronted by a facade of Early English lancet windows. |

|

Footnote 2 - Hospitality in Churches |

|||||

|

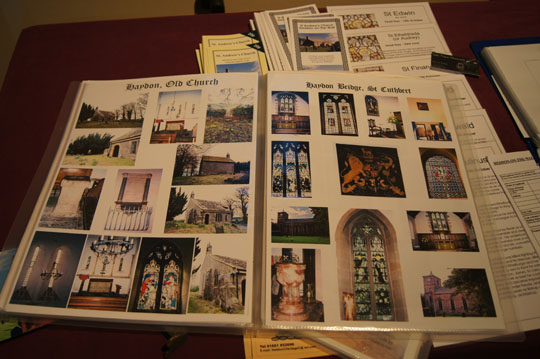

Heddon-on-the-Wall is a candidate for any Most Hospitable Church in England award. In an annex in the north west aisle of the church - a Heritage Centre - there is a wealth of information not only about the church itself but also photo albums of the other churches in the area! The lady in attendance pointed out many things about the church that we might otherwise have missed. This pride in the church for its place in our heritage as well as for its primary role as a place of worship is totally admirable. Heddon is not one of the “big hitters” in the world of church architecture (such as Jarrow, Brixworth and Ludlow for example); indeed it is almost unknown. The person we spoke to admitted that exclusion from Simon Jenkins’s “1000 Best Churches” is a sore point and that their own Diocese has managed to exclude it from its leaflets. But its custodians are proud of what they are caring for and with justification. I cannot help but compare the hospitality at Heddon-on-the-Wall with the attitude at many churches that they belong to the clergy, the churchwardens and the congregation and that access to anyone else is some kind of privilege. Not every church, of course, can find volunteers to show visitors its church. Some have very good security reasons for keeping their premises locked. I can’t help feeling, however, that every church can find a couple of people nearby to hold keys for visitors - they don’t have to be churchgoers - and manage to construct some information boards. It’s a matter of pride. |

|||||

|

|||||