|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

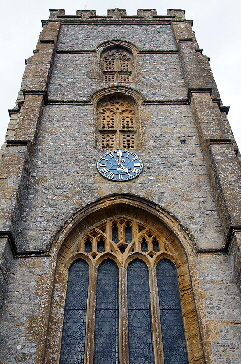

to assume very reasonably that the clerestory itself is Norman but sadly it is a Victorian reconstruction. Even a cursory examination makes you realise that the delightful regular sequence of round-headed windows interspersed with pointed blind arches is too good to be true. Yet this modernisation in no way detracts from a church that is visually delightful and we have to be profoundly grateful to those who were responsible for relocating - and in some cases re-carving - the corbels rather than disposing of them. A north aisle was added in the mid-twelfth century. The south aisle followed in around 1200. The Church Guide says that it is in Early English style but in fact it is a fine example of Transitional style. The arches are rounded and sit on square abaci as do the arches of the north aisle. Indeed, it seems that the masons, even if they had the skills to build in the new-fangled Gothic style, preferred symmetry with the north arcade that was itself still relatively new. The design of the arches is rather more elaborate than on the north side but it is the designs on the carved capitals that really sets the south side apart. Whereas the north side has very simple decoration, the south side has some very entertaining carved scenes. They are secular rather than religious and, moreover. they are in a a quite sophisticated style. If they are reminiscent of anything it is of misericord carving. Apart from the Church Guide the only reference to the date of this arcade is - predictably - Pevsner (although he does not describe it as Early English). For reasons we can’t understand both Transitional and Early English designs tended to eschew frivolous carving. You will search in vain for an Early English corbel table for example. Don’t look for dragons or gryphons. Perhaps it was felt to be “old hat” or even, as Bernard of Clairvaux complained, just a distraction from spiritual thoughts? Whatever, I would not have expected to see these aisle carvings at that date. The Decorated style - and the fourteenth century - saw a limited return to historiated carvings and fine examples can be seen at Oakham in Rutland and Hanwell in Oxfordshire. It could be that the south aisle is “later than advertised” and that symmetry was seen as more important than modern style. Or, conversely, is this an example of a mason clinging to the Norman tradition of carving but doing so in a new, more sophisticated fashion decades ahead of its time? That argument (and Pevsner’s dating) is supported by the chancel arch that seems to be Early English above its capitals. You would have thought this work was carried out at the time of the south aisle, although we can’t know for certain. Either way, in my view these carvings are quite remarkable on an arcade of this period. The Church Guide poses the theory that the work was carried out by masons of the Wells Cathedral workshop. This is, indeed, a theory that resolves all of the disjoints around the Hawkchurch carving. For a start it explains the quality of the carving at a time in a place that it would not have been expected. In his excellent and illuminating monograph “The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture” (2010 - viewable here http://www.queensu.ca/art/sites/webpublish.queensu.ca.artwww/files/files/ReeveCapitalSculptureofWellsCathedralJBAA.pdf) Matthew Reeve talks of “a preceived stylistic antagonism between the capitals themselves and their architectural setting. Commentators on the capitals have sensed a disjunction between a “Romanesque” mode of sculptural decoration within what was a decisively and by some readings definitively “modern” Gothic building...” He believes that the capitals at Wells are from the 1184-1210 phase of building which fits perfectly with the Transitional and earliest of Gothic styles. At Hawkchurch there was no “Gothic building” - indeed as I have already suggested there was a conscious decision that the south aisle should not be in a Gothic style - but the apparent contradiction at Wells of Romanesque style carving at the beginning of the Gothic era is echoed here at Hawkchurch. Matthew Reeve explores the sculptural themes at Wells and notes the broadening out of the sources of such themes from the traditional one of the mediaeval Bestiary, the adoption of lay imagery and also the complete absence of New Testament themes. Again, this is visible at Hawkchurch. Much is made of the West Country School of sculpture centred on Wells and it interesting indeed to see the humble parish church at Hawkchurch bracketed with such noble buuldings as Bristol Cathedral! Having read Matthew Reeve’s book I am convinced that the Church Guide is right in ascribing the sculpture on the south aisle to someone from the Wells Cathedral masonic workshops. The west tower is early sixteenth century. This is datable from the arms carved into a decorative door above the west door. It is very grand and sophisticated with a large west window and carved stone panels at the belfry and very much reminscent of the distinctive style to be seen all over Somerset. further to the west. The south porch conceals the south door which is also reckoned to be Early English and, as the Church Guide remarks, is again carved with a sophistication rarely seen at this period. Its arch profile is almost triangular and very shallow. The profile of the west door is similar so I imagine the south door was altered to match at that point. There’s not much more to be said. The extensive rebuilding of 1859-61 shames the destructive Victorian work at many other English parish churches. It is a very satisfying church to visit. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The view to the east. Note the round-headed arcades to both aisles. Right: The view to the west. By installing a large window in the west wall of the tower and having a mighty tower arch there is a great deal of light coming from what is often the dark end of the church. The clerestory, remodelled in the Victorian restoration, sheds still more light. Note the arcades. The south side (left of this picture) has more elaborate arch mouldings. The difference in the sophistication of the carved capitals on the nearest arches is quite marked. |

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: The chancel arch is decidedly Norman as far up as its carved capitals which, thankfully, were retained when the arch was remodelled during the Early English period. On the north side is a very fine and very Norman carving of intertwined dragons, the tail of one of which is being bitten by a human head. Or is the dragon emanating from his mouth? Above it is the commonplace (but still attractive) floral design. This all looks quite early, maybe early rather than later twelfth century. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: Here we can see dragons or serpents apparently biting the hapless man’s head. He’s having a hard time of it all round! Right: The south side capital has pretty standard Norman decoration with none of the excitements of the north side. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The north side of the chancel arch also has the very unusual feature of a carved scene at the foot of the shaft, in this case a couple of dragons. It is very deeply carved and extremely graphic. I have seen many Norman carvings (just browse these pages) and I really think this is in the first rank yet almost unknown. Right: This is the capital of the western pier of the south arcade. A ram is playing a viol while a goat is playing pan pipes. The Church Guide suggests that these two animals are frequently associated with “sins of the flesh”. The mediaeval bestiary has more than one flavour of “goat” but interestingly it says that the “he goat is a stubborn lascivious animal, always eager to mate, whose eyes are so full of lust that they look sideways...” The “goat” and “wild goat” (as opposed to the “he goat”) are also in the Bestiary and receive a much better press. The Bestiary makes no pejorative references to the ram but the very nature of the creature - the impregnator of flocks - means it did acquire a bad press. The early Church really had no time for sex at all. Bristol Cathedral, also believed to have been the product of the West Country School has a spandrel carving that has a fiddle-playing goat (as well as a bagpipe-playing monkey) so this tends to support the involvement of the School at Hawkchurch. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The main theme here is of a man seemingly reaching out to an animal of some sort. The man is quite well-coiffed! There are plants - possibly vines - on either side and at each corner is a human head. The one to the right has a quite interesting hat. Right: A more rustic human with a peasant’s hate is apparently feeding a squirrel. Flowering plants are to left and right. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A man is feeding a bird of some sort. The Church Guide suggests it is a goose. Right: Oddly, the Church Guide does not mention this carving. It is a reclining figure, but of what? See below. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The ears of this figure suggest it is not a man. Is it perhaps a monkey? And is the hat a Bishop’s mitre? Depicting the clergy in the guise of monkeys was quite popular in mediaeval iconography. It was not intended as a compliment! The body, though, appears to be feathered. There is an image of an ape/bird hybrid at Santiago de Compostella in Spain and it is taken to be the Devil. We can only speculate about the meaning of this carving, however. Right: The squirrel-feeding peasant. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The viol-playing ram and the goat. I think the goat may be playing a shawm. Right: The eastern respond of the aisle has a more religious theme. The tonsure of this man tells us he is a cleric and he is holding a book. The Church Guide suggests that the monk may be referring to Cerne Abbey which was the patron of the church here. This is, again, a very fine piece of carving. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: At the opposite side to the monk on the eastern respond is this un-tonsured man holding a scroll which might well represent a figure from the Old Testament. Right: What a difference a few decades make! I am a great fan of Romanesque sculpture but there is no denying the advances made in the carver’s art. This is a capiital from the Norman north arcade. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: You can see here that the the two arcades are very similar apart, that is, from the carvings. The easternmost arch of the south arcade, however, (right) sees the mouldings of the arch sweeping down into to form multiple piers which is a level of sophistication beyond the north arcade and which presages the Gothic sophistications to come. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another view to the west. centre: The enormous tower arch which opens up the entire church to the light from the west window. Right: The west door and window. Note the decorative panel above the doorway. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On the decorative panel above the west door you can just make out five sets of arms. Second left is the Staffordshire Knot - surely one of the most instantly recognisable of all county crests? This refers to Cecily Bonville, Marchioness of Dorset, who married her second husband Henry Lord Stafford in 1530. Her arms can also be seen in the Dorset Chapel of Ottery St Mary. At the right hand side are the four lozenges of the arms of Montacute. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south porch with the curiously-shaped south door beyond which matches the design of the west door. One of the delightful features of this church is the mixture of stone materials. Most of the exterior is of Greensand chert rubble. The Victorian stone courses such as can be seen around the clerestory windows is of Ham Hill stone from Somerset. You can see on this website a description of the church of Stoke-sub-Hamdon which is near the quarry, made of the same stone and which is also a Norman church. Right: The church from the north. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Top Left: A section of the south clerestory. The carvings are Norman but most of this composition is Victorian. The restorers made a marvellous job of creating faux Norman windows interspersed with narrow blind arches. This is very like a Transitional composition and is a very fine piece of restoration indeed. The stone course which overlays the corbels is also Victorian. If only all Victorian restorations had been so sensitive and so skilful. The corbel table here is not well known, yet it has some extremely interesting carvings that have survived better than those on most parish churches. As always, I am not going to speculate on what they represent - I’ll leave that to more imaginative commentators - but I am showing a few of the real beauties here. Top Right: On the left is a cleric holding a shepherd’s crook and a book. For my money that’s as good a Norman corbel as you will see in England, Look at the detail and at the state of preservation. Right Middle: Two characters in fond embrace. Or is one strangling the other? Bottom Right: Now this one is really intriguing. I think we can all agree that in the right hand corbel we have a woman (on the left) and a man. The carving is not as sharp as it was (although still way better than at most churches) and I am not one that looks for sexual symbolism in everything (there are plenty that see it everywhere, let me tell you!) but is that woman’s hands touching her - ahem - pudendum? She had a wicked grin on her face. Is this a sheela-na-gig? I’m not sure about the bloke, though. He looks a bit miserable. I’ll leave you to decide why.... |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left Hand Pictures: Two more unidentifiable corbels. The top one seems to have been recarved at the time of the restoration and you can see that already the stone has performed much worse than the original stone that has stood outside for eight hundred more years. The lower carving seems to be of a human face with an animal’s body - a popular Norman motif. You can’t really see it in this picture but there is what looks like a kind of an eye between his legs although I think that’s probably an optical illusion. You know what? When I wrote that I really didn’t notice it was a pun! Centre: The church from the north side. The corbels on this side have not survived as well as on the south side which is not altogether surprising perhaps. They are not quite as interesting either. Right: The west tower. Note the Somerset-like stone bell chamber louvres. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||