|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

fragments of original glass survive in many of them. They are beautiful and not to be missed. The core of the nave was probably contemporary. The aisles and tower, however, are Perpendicular dating from the late fourteenth century. The fifteenth century saw an extension by three feet if the south aisle and the building of the north porch. The sciapod is actually not too easy to find. That is because it is on a bench end and before you find it you are distracted by the rest of the benches. Each has carved bench ends and poppy heads and armrest carvings of great interest. Even the backs are extensively carved. They are so typical of this part of Suffolk but this is a particularly fine and extensive collection. |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: Entrance here is via the north side. They didn’t go in much for undersized porches in Suffolk. This fifteenth century one is cavernous but quite austere. One wonders why the wanted it built so high? The doorway is probably a century older coinciding with the building of the north aisle. Centre: Looking towards the east. This really is a long church! Benches - with their carved ends and poppy heads - give way to box pews which give way again to grand box pews for the side chapels. Then you get a few loose chairs near the east end into the bargain. The population of Dennington? Less than six hundred in 2011! Right: The view to the west from beneath the lofty chancel arch. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The famous “sciapod”. According to “A Dictionary of Fabulous Beasts” (Barber & Riches, 1971) Sciapods are “Men with one foot so large that they would lie on their back and use it as a sunshade. They were usually described as one legged, and very swift, though a four-legged species which used one leg as a shelter was also reported. They lived on the fragrance of fruit only, and carried fruit with them when they travelled for this purpose; if they breathed corrupt air thaey died. Also called Monoscelans”. Don’t you love that “also reported” bit? By whom, one wonders? John Timpson in his “Country Churches” says the church is reputed to have been built on the site of a druid temple so something the sciapod’s unique appearance her might have had something to do with it. About eight hundred years later? Yeah, right! Wikipaedia cites many ancient references beginning with the Greeks and I especially like this one by Giovanni de Marignolli in the first half of the fourteenth century so only a few decades before the carving at Dennington .Quoting from his travels from India: “The truth is that no such people do exist as nations, though there may be an individual monster here and there. Nor is there any people at all such as has been invented, who have but one foot which they use to shade themselves withal. But as all the Indians commonly go naked, they are in the habit of carrying a thing like a little tent-roof on a cane handle, which they open out at will as a protection against sun or rain. This they call a chatyr; I brought one to Florence with me. And this it is which the poets have converted into a foot”. So Giovanni saw his first parasols! Note his airy observation that there might be an individual monster “here and there”! Lord knows where a carpenter heard about sciapods and why he thought one appropriate material for a church in Suffolk. We can only be grateful that he did. Right: This is a particularly rustic set of benches that have been relegated to the south aisle. Theyl ook monstrously uncomfortable but I guess they are rarely used now. They have no carvings on their side panels but, as elsewhere in the church, they have their carved animals. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The parclose screen of the north chapel. Right: The parclose screen of the Bardolph Chapel on the south side and directly opposite its northern counterpart creating a symmetrical composition unique in a parish church. In both cases the balustrades are extant and note the way that both wrap around the columns of their respective arches. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Tracery on the north chapel parclose screen. It dates from about 1450 and it is interesting to see how the carpenter has adopted the cusped tracery style of Perpendicular windows. Perpendicular style was to some extent a response to the need for a degree of standardisation after the great Plagues of the fourteenth century had reduced the ranks of the stonemasons. We see here, however, that other craftsmen were moved to copy the style themselves and we will see this gain when we look at Dennington’s fourteenth stained glass in the chancel. The colouring of the screen was renewed in 1845 and the screen itself is totally original. Note the bunch of grapes motif that recurs near the bottom of the piece. Right: The parclose screen from within the south Bardolph Chapel. The tracery style is similar but not identical to that of the north. Note the delicacy of the carved adornments below the cusped tracery. The survival of the lofts on both chapels is quite remarkable. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: North chapel screen tracery. Right: Parclose screen on the Bardolph Chapel showing the access doorway behind. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A selection of the bench end armrest figures, Otherwise known as “Fabulous Beasts and Where to Find Them”. I’m not going to speculate on what they are (although I particularly love the eagle (?) with the chicks in the nest. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking across some of the benches towards the north door. Right: Looking across the benches towards the north chapel. The bench ends themselves are heavily decorated but don’t have the historiated carved scenes that were popular in, for example, the West Country (see, for example, North Cadbury in Somerset). They, in turn, did not favour the arm rest figures popular in Suffolk. We can never under-estimate the importance of local craft traditions in medieval churches. The poppy heads themselves are elaborate but, again, purely decorative. With so many it is remarkable how the carpenters ensured no two were identical. Note the decorative carvings on the backs of the benches too. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: The Bardolph monument within the North Chapel. Sir William Phelp (Lord Bardolph) fought with Henry V at Agincourt and was briefly Governor of Calais - a post of great prestige. His wife was Lady Joan. She was the daughter of Thomas Bardolph, the fifth earl. Thomas was part of the faction led by Henry Percy Duke of Northumberland that tried to overthrow Henry IV (whose claim to the throne was, admittedly, somewhere between sketch and non-existent). It didn’t work out well for Thomas. After the rebels were defeated the first time round he fled to France. returning three years later. He hooked up with his old mate Percy again and died of his wounds after the Battle of Bramwith Moor. Compared with Percy he got off lightly: he was hanged drawn and quartered. The states were forfeit, of course, but some time later some of them were returned to Joan and her husband who clearly was a man more attuned to the political climate! Monuments of this sort are a great gift to students of mediaeval costume, of course. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The effigy of Lady Joan. Like her husband she wears a necklace with an “s” pattern. Centre: The south side of the chancel has this this composition of piscina, and sedilia. Oddly, two of the obligatory three seats are placed awkwardly below a window while the third has a much more elaborate setting. Right: This single sculpture adorns the end of a string course to the right of the priest’s door. The Church Guide suggests an unidentifiable apostle. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The priest’s door. It is unusual in several ways. Firstly, it is quite ornate. It has a v-shaped arch and it is adorned by a set of three carvings. Traditionally the insides of priest’s doors are quite plain affairs. The are two label stop carvings: a bishop to the left, a pope to the right. Above it is a strange dragon-like sculpture. All very odd! Note the “apostle” carving to the right, Centre: The prestige end of the sedilia. Right: Looking up the south aisle towards the Bardolph Chapel you can see the decorative seat backs. Note also the plain eighteenth century box pews beyond them. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: The Bardolph Chapel has some superbly-preserved mediaeval encaustic tiles. with leaf patterns. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A close-up of one of the mediaeval tiles showing a cusped cross design, Right: A St Peter’s Pence box carved out of a single piece of wood. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: Pews associate with respectively the south and north chapels. I haven’t been able to find out what the various coats of arms mean. Once again the symmetry of these pieces bespeak of their being contemporary with each other but also note again that the designs are not identical. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

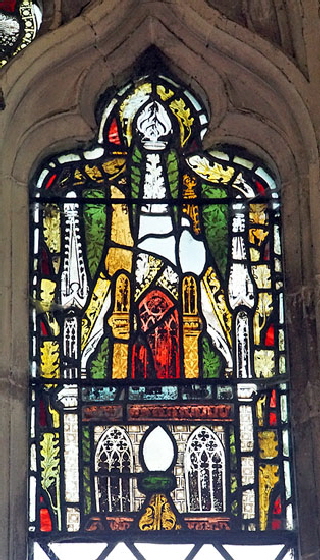

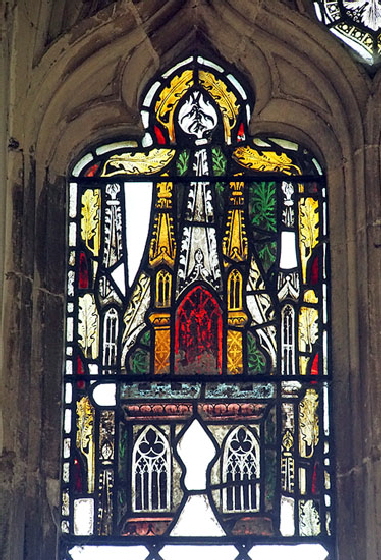

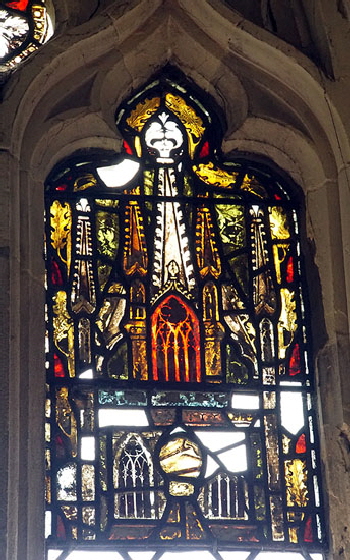

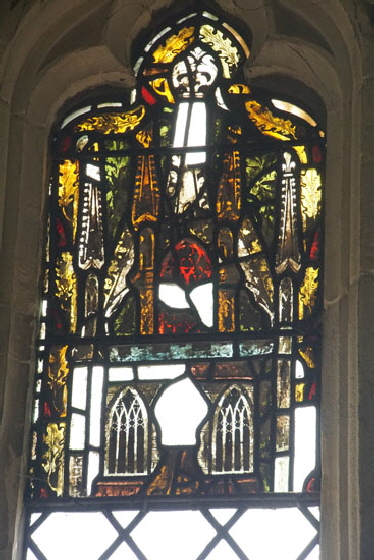

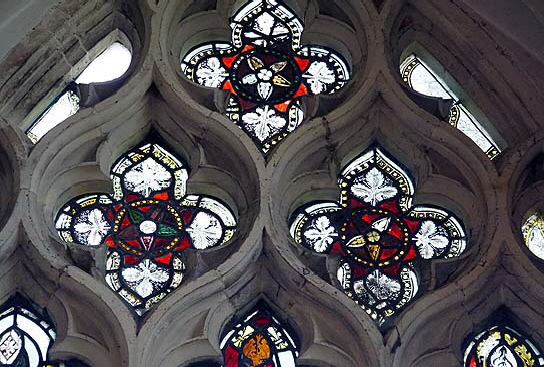

I can rarely get too excited about coloured glass. Too much of it is meretricious rubbish from the nineteenth century. Sciapod apart, however, it was Dennington’s chancel window glass that most excited me. As you can see it has not survived totally intact but a lot has and it dates from the building of the chancel in 1330. Apart from the beauty of the craftsmanship itself, what excites me is that here we have a glazier recording the architecture of his day. All of these panels show windows and pinnacles. It is a text book study in the Decorated style window tracery of its time. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The configuration of the windows here is that there are three vertical lights with painted glass at their heads. The tops of the windows have reticulated tracery and each of the resultant quatrefoils (and part-quatrefoils) has painted glass. Right: The standard design for the reticulated glass panels is of a central star desight surrounded by four leaves. The leaves are repeated between windows but the stars and the colours vary. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: More quatrefoil window inserts. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another unusual, i not unique, feature of Dennington Church is this hanging pyx. A pyx was used to hold the holy sacrament. This one hangs over the altar and an be brought down to usable level through tugging on a counterweighted cord. Centre: Looking along the north aisle to the chapel. Right: The decorative designs that support both the north and south aisle ceilings. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: One of the fascinating aspects of the Bardolph monument is that Lady Joan’s feet rest on a wyvern, while her husband’s rest on an eagle. A dog was far more common. Right: Looking along the south side. Note the regularity of the windows and the meanness of the clerestory. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south east. You can see here how the reticulated tracery of the chancel which was built in the Decorated style gave way to the less flamboyant and more formulaic Perpendicular style visible in the east window of the south aisle. Right: The north side. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The priest’s door from the outside. Like the inside it has been adorned with bishop’s heads, one now disappeared. Right: The hefty tower dates from the fourteenth century and is a real bruiser. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - Church Guides |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I have a filing cabinet stuffed with church Guide Books, arranged by county. Unless a guide is ridiculously expensive - and one or two are - I always buy one as a sort of donation to church funds. When I started this site I seriously thought of giving church guides marks out of ten. I don’t because church guides get replaced and the information would soon be obsolete. More to the point, though, people don’t decide whether to visit a church depending on how good the book is so why bother? So I haven’t. Also I don’t like to embarrass people who have done their level best with limited resources of time and money. Often it is patently down to one enthusiastic local historian or member of the clergy. I write about it here because I am struggling to remember a church that is so let down by its Guide Book as Dennington. Sorry, Dennington, but it is true. The church is a treasure house, the guide book a scrappy n-th generation photocopy of a very brief monochrome document written by the (actually very well-respected) Roy Tricker in 1985 - and that was the third edition! It has two line drawings, a plan of the church and various very brief descriptions of what’s inside. There is not a single photograph. The printing bleeds through the pages. As it happens, the guide is useful. It points you in the direction of everything you need to see but it shows no pride in the place. Some churches move heaven and earth to make their church sound like an interesting place to visit even when it is quite ordinary. But to them it is special and they want you to feel their pride. Dennington, sadly, makes sow’s ear out of a silk purse. They have a great story to tell, so much to be proud of but for whatever reason they do the barest minimum. Am I being unfair? Well, let’s see. I spent about an hour and a half at the church. I took over a hundred photographs. On this page there are fifty-eight photographs (I think). Tarting them up and making them small enough for the web took about two hours. Writing the text using a variety of sources on and offline - and, yes, the church guide was amongst them - took about ten hours. Let’s say two days of effort. I don’t have any direct interest in this church but it was a commitment I made because I want people to know about our wonderful parish church heritage. It’s about the three hundredth I have written about on this site. I know the web allows me to go to town without incurring extra costs but nobody is asking a church to have fifty odd colour pictures, or any at all for that matter. Just something nice and a bit professional. Dennington only has to write about the one church. Hasn’t anyone there had a couple of days to spare in thirty five years? I am sorry if this sounds like a rant. Dennington is not unique. It’s just that the church is so wonderful and It just pushed me over the edge to say what I feel. Guide Books don’t have to be expensively-produced but they need to look as if they have been produced with care and pride. A six hundred year old building deserves that, don’t you think? If our communities can’t show any pride in their church heritage then how can we expect taxpayer funding to help preserve it? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 2 - The Shakespeare Connection |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Did that name “Bardolph” sound familiar? It did to me. Shakespeare had a Bardolph in his “Henry IV Pt I” and he reappears in “Henry V”. As a friend of Falstaff he also appears briefly in the “Merry Wives of Windsor” This is the Wikipedia entry: “Bardolph is a fictional character who appears in four plays by William Shakespeare. He is a thief who forms part of the entourage of Sir John Falstaff. His grossly inflamed nose and constantly flushed, carbuncle-covered face is a repeated subject for Falstaff's and Prince Hal's comic insults and word-play. Though his role in each play is minor, he often adds comic relief, and helps illustrate the personality change in Henry from Prince to King.” It seems extremely unlikely that Shakespeare was unaware of the Lord Bardolph who opposed Henry IV in reality, especially as he changed the name of the character from “Russell” in early editions because of the risk of offending the powerful family of that name. In Henry V he has become a lieutenant but he is convicted of looting during the fall of the town of Harfleur. Although in the play Bardolph was a friend of the youthful Henry the ming makes an example of him and has him hanged. In fiction as in life, Bardolph came to a bad end. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||