|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Purgatory) was granted by Boniface IX to anyone giving money to the maintenance and conservation of the church; another sign of Hanborough’s privileged status. This led to a further period of expansion and remodelling in the “modern” Perpendicular style. The tower was enlarged so that the tower arch we see today incorporates only the base of the early English one. The arcades were rebuilt to the impressive height we see today. It has been suggested that the arcade is so similar to that at Northleach Church in Gloucestershire that they were designed by the same master Mason. I believe that the clerestory dates from this time as well (as does the Church Guide) although I have also seen it dated to later in the fifteenth century. I find that very unlikely as clerestories were all the rage in the early fifteenth century and the aisles in Hanborough were by now very large. Later in the century the rectangular windows replaced the earlier ones in the aisles and quite possibly in the clerestory as well. Also at the end of the fifteenth century the church acquired its second “treasure”: its caved wooden screens. Rood screens “offended” post-Reformation Christian doctrine on three levels. Firstly, they by definition supported a wooden “rood” or cross usually with Christ crucified and two other figures, such as the Virgin Mary or an Evangelist (we don’t really know as they’ve all gone!). These representations were seen as idolatrous and as far as I know none survived in situ. Secondly, the lower part of the screen was generally painted with images of various saints. These also were seen as idolatrous. Finally, the concept of separating the “mysteries” of the Eucharist and the priest from the great unwashed in the nave was seen as against the congregational principles of Protestantism. Hanborough does not, of course, retain its rood. Its painted panels have been obliterated. Yet the screen remains. It is by no means unique in its survival but it is unusually complete and original. How did it survive? Well, as long as the priest conducted his business in front of rather than behind the screen perhaps it was tolerated. Or perhaps it was stored until more propitious times. Who knows? |

|

|||||||||||

|

Let’s start with the tympanum on the north doorway. As you can see, this one has survived the last nine hundred years well. That is because there have been porches on both north and south sides since the thirteenth century. North porches at this time are unusual because, as I have reiterated on many of these pages, the north door was intended not for the ingress of parishioners but for the egress of the the Devil during baptism. So why was it built if, as most people believe, the “Devils Door” was eschewed by parishioners? A very interesting paper by Nicholas Groves, Alumnus in Theology at the University of Wales, perhaps throws some light on this and I discuss it in the footnote below. Anyway, the principal figure in this composition is refreshingly obviously St Peter with his keys. He has a kind of swagger about him, doesn’t he? “I decide who goes through this door, sonny....”! At his feet (on his right as you view this picture) is the cock that crowed on the three occasions Peter betrayed his Master. It seems he wasn’t allowed to forget his own transgressions either! Equally clear are the winged bull of St Mark and the Agnus Dei. We shouldn’t be too surprised at the very decent representation of the lamb - although it was clearly beyond the skills of many a Norman tympanum carver - but the quality of the lion is a surprise. In fact this is a very fine piece of Norman art indeed although maybe Peter’s face is a bit of a let down! |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: The tympanum and the surrounding archway. Right: The church looking to the east. Note the height of the arcades and also the three rood screens. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west. This end of the church is very open and airy with, as you can see, the current main entrance, a west window and a very large open tower arch. Centre: The chancel with its fifteenth century Decorated style east window. Right: The north chapel. In the two recesses you can see decorative fifteenth century wall painting. The Church Guide points to the white roses on a red background and speculates that it was a sign of the reconciliation between Lancaster and York after Henry VII’s victory over Richard III at Bosworth. I think maybe that’s a little tenuous. Henry wasn’t that conciliatory. I’d have made those roses red! |

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

Left: The north wall of the chancel with the lancet windows that so definitively point to early English provenance. Note the brass in the recess to the left of the priest’s door. Pevsner suggests this may have been an Easter Sepulchre but they are usually on the north side. Centre: The north wall of the chancel. Is one of these recesses Pevsner’s easter Sepulchre? Above the monument you can see the head of a lancet window blocked by the building of a vestry on the other side Right: On the southern side of the south aisle is this comparative rarity: a still functioning rood screen door. How many empty rood stair doors are there in England? Note the fine decoration on the screen itself. |

|

|

||

|

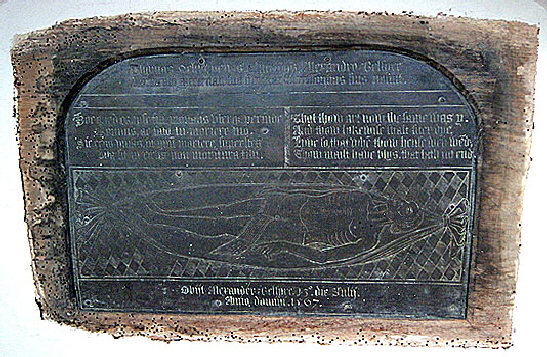

Left: The brass within the niche of the north chancel wall. This is one of a genre of macabre memorial tablets that became extremely popular. The deceased is shown as a skeleton with both the implied and express message “As I am, so shall ye be”. Quite why this reminder from beyond the grave was deemed necessary, I don’t know. This one commemorates Dr Alexander Belsyre (d.1567) who, the Church Guide tells us, was the uncle of the rector Thomas Neale who was the incumbent from 1558 to 1567. The Church Guide says that Belsyre was an open “recusant” - a Catholic who refused to attend Church of England services. This was punishable by fines or imprisonment and Belsyre was eventually ordered not to travel more than two miles from Hanborough. Neale, on the other hand, was a closet recusant. Holding such views whilst performing the office of Anglican priest must have been perilous indeed even at a time when Elizabeth’s strictures against Roman Catholics were much milder than they would let become after the various plots and attempts on her life. He neatly sidestepped this by appointing a conformist curate! Were some of Neale’s parishioners recusants too? Did he hold secret Catholic masses within or outside the church? He wisely resigned in 1567 rather than face close examination of his beliefs but not before inserting this brass memorial to his uncle (who was actually buried in Yate, Gloucestershire) within Hanborough Church. The epitaph says: “What thou art now, the same was Y. And thou shalt likewise shuer dye. Ly(v)e so, that when thou hence welt wend, Thou maist have blys, that hath no end” . That’s not a bad little verse, is it? It’s all a darned good story to boot! Right: The chancel screen. Note the defaced lower panels that probably bore forbidden images of saints or apostles. |

|

|

Detail of the chancel screen. There is enough of the original paint remaining to show what a magnificent piece of work this would have been like when new. |

|

|

The beautiful south screen has a vine scroll design and is clearly very different from the chancel screen. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The north east of the church. Here you can clearly see the original windows of the north aisle dwarfed by the later Gothic ones. The whole of this east end can be described as “lofty”. The roofs of both aisles and chancel are very tall so that the clerestory is unusually inconspicuous. The Norman aisles - unusually - were never widened so that the heightening of the walls make them somewhat anorexic! Right: A MYSTERY. How I love them. You can see this window in the left hand picture, high up on the north aisle wall. What then is this metal ring for? Not for tying a horse or mooring a boat! Not, surely, for hanging stuff from (it is very high up). Did it have a lamp that was lit by a taper on a long pole? Well ok that’s far-fetched - but can you think of anything more plausible? It doesn’t look very ancient. |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: The south east aspect. Note the tall lancet windows of the chancel. Note also the original Norman window at the east end of the south aisle and the priest’s door. This picture really demonstrates the great height:breadth ratio of this end. It was a lovely summer evening when we visited with the honey coloured Cotswold stone bathed in summer evening light. Right: The east window. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: The east window’s label stops are, as is so often the case, Queen and King figures. So - which ones? Well, surprisingly perhaps, the window was installed at a time when kings were beardless. Henry VIII had a beard but nothing like this. So it look rather like an idealised one or else a Victorian addition. Unless of course you know any different.... |

|||||||||||||

|

Footnote - North Doors Continued |

|||||||||||||

|

I have previously discussed this topic under Whitcombe and Luppitt. Broadly, it is generally believed that north doors were intended to allow the Devil to exit the church during baptism. This explains why, once exorcism was no longer part of the baptismal rite, north doors were so frequently blocked. |

|||||||||||||