|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

guess at, is at a pronounced dog-leg from the tower. It has been suggested that this was to avoid an obstruction but perhaps a good old Anglo-Saxon bodge job is equally possible. “Ah”, you might think, “but I know of other churches with a so-called “axial towers”. What sets the Bartons apart, however, is that their towers were their original naves. Axial churches had naves west of the tower and the ground floors of their towers were generally used to house the choir. The tower at St Peters has a footprint larger than either of its wings. Its apparent size is much diminished by the size of the gothic extensions to its west and by the loss of what would have been a lofty broach spire with a roof of wood shingles. The church went through many phases of development. The Normans extended the tower upwards and extended the chancel eastwards with an apsidal end. Then there were various phases of gothic additions that I do not intend to explore here because they pale into insignificance against the tower. You can see from the picture above, however, that the south aisle windows are in reticulated Decorated style, whereas the later clerestory has bog-standard Perpendicular ones in, it must be said, rather magnificent style. The church has been extensively restored by English Heritage and it is because of this that I failed to get access to the inside on two out of three visits! If you do visit be sure to buy their very informative leaflet. |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

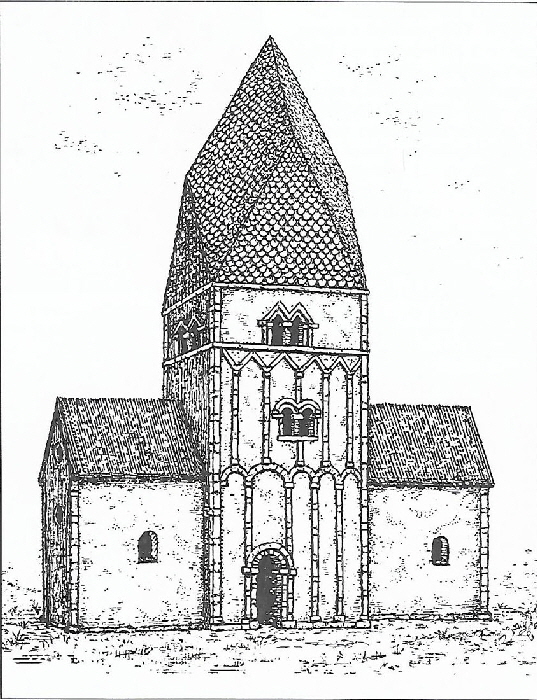

Left: The tower as it is now with its western baptistery. Right: The church as it was built. The tower originally had a broach spire - a device used to seat an octagonal spire on a square tower. This picture - courtesy of English Heritage - shows just how tower-centric this church was, possibly reinforcing the view of the eminent architect Hugh Braun who argued very convincingly that this church plan was influenced by Byzantine (that is, of the Eastern Roman Empire) architecture and was not Romanesque (that is, Western Roman) architecture. Braun argued that the masons of Western Europe lacked the ability to build Byzantine domes and instead used equally imposing towers. The spire was removed by the Normans and replaced by the unfaced rubble stone top section that we see today. As at Earls Barton there are bifora and we also see those fascinating double triangular-headed windows that are perhaps the most iconic symbols of the Anglo-Saxon style. Again as a t Earls Barton there is an original south doorway. There are two courses of pilaster strips, the lower one with arch-shaped headings and the upper course with triangular shapes. This is a rather less complicated scheme than at Earls Barton that has some quite fussy pilaster mouldings. The challenges faced by the masons with their carpentry-type tools in making the pilasters reasonably regular geometrically is plain to see. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Left: One of the bifora. Interestingly, Braun hails this also as being a Byzantine architectural device that owed nothing to “Romanesque”. Note the pair of balusters. As at Earls Baron the sills follow the courses of the horizontal string courses. Lead has been added presumably to stop the masonry of the ledges from deteriorating through rainwater. Right: The double triangular openings also have turned balusters. This style of opening reflected the pre-Conquest masons’ search for simplicity of construction. Arches are complex to produce to produce and you will note in the picture (left) that the arched window openings here are carved from one or two blocks of stone which is much simpler than using individual arch stone (“voussoirs”). Similarly, triangular heads need only straight pieces of stone and the whole composition is all very much as a carpenter might have devised. It has always seemed to me, however, that the pre-Norman masons understood perfectly well that the triangular head was not reliable where the span is greater. You do not see triangular-headed chancel arches or tower arches, for example and even most doorways are round-headed unless they are very narrow. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Left: For comparison, this is a Norman biforum from the top stage that houses the bells. You can see that the masons have used small voussoirs to construct the arches. The baluster is altogether less crude (although one might add perhaps less ambitious) than their Anglo-Saxon counterparts. Taylor & Taylor, however, believed that this topmost stage was Norman in style but that it was dated either immediately before or immediately after the Conquest, citing amongst other things that the arch stones are still flush with the wall. . Right: The church from the north west with apologies for the distorted perspective produced be the wide angle lens I used. There is little difference between the north and south sides of the tower but note that the doorway here is triangular-headed. The baptistery is the same on both sides. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

A tale of two doorways. Left: The arched south doorway. Even the Anglo-Saxon masons jibbed at trying to find a single stone block to form the arch so they have used voussoirs of more-or-less regular sizes. Right: The triangular headed north doorway. It could almost serve as a template. There is no suggestion that these doorways are of different dates. The masons just seemed to want to show a bit of variety. Note the way that both doorways utilise the vertical pilaster strips, |

|

|

|||||

|

Left: The church from the south west showing the west end of the baptistery. The first thing to note is that there are signs of a filled-in western doorway which visually looks somewhat higher than those on the northern and southern sides of the tower. As Pevsner noted, however, the wall itself has clear been disturbed so we can’t be sure. There are two circular windows on the west wall which are original. The upper window would have allowed light into the upper room which was probably used by the priest or for storage. Note the fine “long and short work” at the quoins (corners!). Interestingly. Pevsner suggested that both the presbytery and the lost Anglo-Saxon chancel pre-dated the tower itself, although he did not elaborate on what he thought might have linked these cells before the tower was built. I have seen no supporters for this idea that seems to me to have been somewhat fanciful (with apologies to those readers who believe that if Pevsner says it’s Wednesday then it’s Wednesday). In part the theory seems to have been spawned by the suggestion that the western cell is not fully “bonded” to the tower (that is, the masonry of the two cells is not fully joined) and that he western cell is therefore earlier. Taylor & Taylor repeated this theory but could see no real evidence for it. An earlier edition of the Church Guide suggester that the baptistery pre-dated both the tower and the chancel. Again there is no real evidence although it would explain the existence of a wester doorway, Right: I have taken the liberty of nicking this fascinating picture from English Heritage’s leaflet. The picture was taken in 1980 during excavations at the time, incidentally, of my own first visit when consequently I couldn’t get in! Here you can see the foundations of the Anglo-Saxon and Norman churches. The apsidal sanctuary of the Norman church is very obvious at the bottom of the picture. Beyond that you can the square chamber of the Norman chancel. Beyond that is the old Anglo-Saxon chancel that was about the same size as the western cell. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

Looking towards the west of the interior. As we would expect, there is a double triangular opening matching those on the other three sides (although the western pair has been filled in). The doorway above the chancel arch was to the upper chamber of the old chancel. The apex of the chancel’s Anglo-Saxon gabled roof surrounded this doorway. The Norman chancel was higher and its roof interrupted the triangular windows before the shallower and higher clerestory of the present nave revealed the whole window again. The tower doorway is, of course, original too. If you look closely you can see “put-log holes” into which the Anglo-Saxon scaffolding would have slotted. How awesome is that? |

||||||