|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Addition Little Kimble (Buckinghamshire) Wellingborough, St Mary (Northants) Great Kimble (Buckinghamshire)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

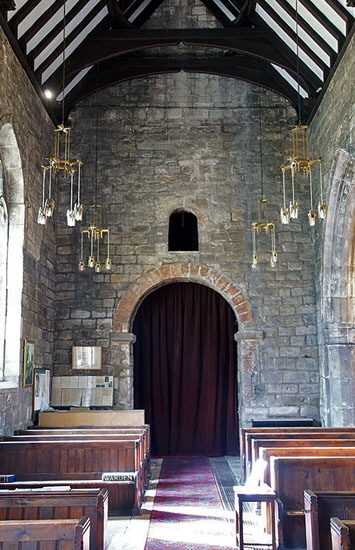

obvious sign is the famous south door into the west tower, about which more later. The Anglo-Saxon part is, in effect, a church within a church. Much of its nave survives as today's nave but its original chancel has been replaced by a much longer thirteenth century one and the entire length of nave and chancel is paralleled on the north side by a fifteenth century north aisle and a fourteenth century lady chapel. In essence, if one were to bisect the floor plan (less the west tower) vertically and horizontally to form four smaller rectangles, the remaining Anglo-Saxon part occupies roughly the bottom left hand rectangle plus the lower part of the west tower. The chancel arch is original Anglo-Saxon. This is easily ascertained by the characteristically crude stonework to either side. The impost blocks have some ornamentation but these were a subsequent (and dubious) addition. The voussoirs to the arch above are to my eyes unusually regular and hint at possible restoration at some point in history. |

|

|

|

|

Left: Looking east towards the chancel. Interestingly, when you enter the church it is not immediately obvious whether this is the chancel or a south aisle since the north aisle itself stretches as far as the east end and its gothic arch is somewhat more imposing. The south west quarter of this church, however, is the original Anglo-Saxon part of the church and still forms the chancel of the modern church. The simple chancel arch is itself Anglo-Saxon. Centre: The west wall is Anglo-Saxon and as far as the stone course that is level with the tops of the south wall and the aisle arcade. The window space is Anglo-Saxon but the tower doorway is Norman, although with its plainness we could all be forgiven fro thinking it to be Anglo-Saxon. Within this space there would have originally been a west door that would have given access from what was then a porch into the nave itself. Nowadays, of course, entry is from the south side. The window reflects the fact that the porch was of two storeys, the floor bring at a level just above the imposts of the tower arch. Right: Looking from the north aisle into the north chapel. This was originally the Lady Chapel before the Reformation proscribed such things. This was fourteenth century and in the Decorated style, although the east window has clearly been replaced. Prior to the building of the aisle this north chapel must have been a rather inelegant addition to the floor plan. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west through the chancel arch. The jambs are clearly Anglo-Saxon although the stonework has clearly been altered on the north side to accommodate the large squint. The imposts have what is very obviously Victorian decoration. The voussoirs of the arch are beautifully cut and laid. HM Taylor was of the view that these are original Anglo-Saxon but, reluctant as I am to gainsay such a great authority on Anglo-Saxon churches, I do wonder if they have not been, at least, relaid. Interestingly, the imposts have a curved profile on the inside matching the design of those on the south-west door (see below). It seems to be agreed that those pesky Victorians saw fit to add decoration to imposts on both the south west door and the chancel arch. One wonders why they would have gone to that trouble? One also wonders why the decoration on the chancel arch is, if nothing else, neat while that on the doorway is such a mess? Centre: The hefty squint from the north aisle into the chancel looking towards the west. Right: The north west corner of the church. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel of AD1240. The east window is a Victorian replacement of two Early English lancets.. The south windows to the right are original. Note the broad two-bay arcade into the north chapel which give such an open feel to this church. Right: The view to the west through the north aisle arcade. Above the south door you can see the reamins of filled-in the porticus doorway/window. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

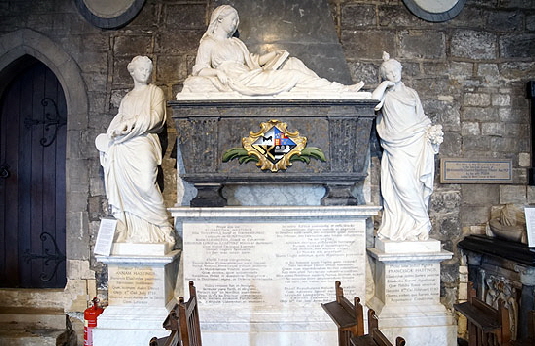

Left: The chancel from the north chapel. Right: The monument to Sir John and Lady Lewis in the north west corner of the church dates from 1677. Sir John was a factor in the fabulously wealthy East India Company and became very wealthy himself (of course!). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south doorway with the porticus opening above, There is no sign of a floor to an upper storey. Above Right: the chancel arch impost block with Victorian decoration. Lower Right: The impressive monument in the north aisle. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: Built into the inside wall of the north aisle are these two Anglo-Saxon stones that are assumed to be the arms of a churchyard cross. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west wall has this re-used stone upon which a butcher’s cleaver was carved. It is believed to have been the side of a Roman altar. Right: The aisle arcade has remains of filled in Anglo-Saxon windows that would once have been on the north face of the church. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The churchwarden Audrey Taylor informs me that this font was found buried in a field nearby! Such was the fate of many a font. it seems. Is it Anglo-Saxon? Is it even Christian? I’m pretty sure it’s both, but we can’t rule out Norman origin. Notice the bulging projections on each corner which was a feature of many early fonts, often adorned by carved heads. Right: On the south west corner of the tower is this curious arrangement of masonry. Nobody else seems to have remarked on it and I am possibly “seeing things” that don’t exist but it looks like stonework recovered from an Anglo-Saxon window, especially the rounded section. Mind you, it’s located in the original Anglo-Saxon section of the tower so it doesn’t seem as if it could have been re-used in its construction. This part does look like it might have been repaired, however. Could it be stonework from a window of an upper floor in the original south porticus? Yes, maybe I am seeing things! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south wall of the Anglo Saxon nave shows blocked windows either side of the perpendicular style replacement. Note the lintel of the western window which is carved from a single block of stone. Note the carving of a head inserted above the present window. Right: The southern exterior of the Early English - and heavily buttressed - chancel. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The controversial - but indisputably Anglo-Saxon - south west door into the tower. It is only 5’7” high. Compare those massive and crude voussoirs with thos of the chancel arch. Note the enormous jamb stones. The decorative strip around the outside is the main source of debate. Centre: The south side of the tower showing the position of the doorway. To its right are two small Anglo-Saxon windows with, like those of the chancel, lintel stones cut from single blocks. The two windows reflect the two floors in the original porch. Right: One of the tower windows with, of course, a modern sill. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The top section of the outer moulding of the door has rosette carvings that are obviously modern. Right: The impost blocks are another matter. The carving is crudely executed and it seems to me to be unlikely that it was produced in the Victorian era. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The upright parts of the south east door moulding are decorated with vine scroll. This is a decoration very much in keeping with the Anglo-Saxon era. It does seem likely that the Victorian restorers simply copied what was there before. Centre: The tower from the south. Right: The south door. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This is the carving placed over the perpendicular window on the the south wall. Second Left and Second Right: These two coats of arms are label stops on the west window. They are rather nice but I don’t know whose arms they are. The window itself is a Victorian replacement so presumably these arms are also from that era. Far Right: The top belfry stage of the tower (but not, of course, the battlements and spire) was added by the Normans in completely different stone that still stands out to this day. They also added a hefty corbel table. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south. The porch stands where the porticus originally was. Right: The north side is, sadly, unloved and neglected. Shame. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Norman stage of the tower on the south side showing the corbel table, Norman bell opening and later battlements, pinnacles and gargoyles. Right: The east end of the church. Looking at the lie of the land it is unsurprising that heavy buttressing is needed on the south side. It’s a common issue as churches grow over the centuries. This little church started life as a nave, a porticus, a two storey porch and a small chancel. Adding an aisle and a chapel on the “uphill” side was obviously pushing things literally and figuratively. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||