|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

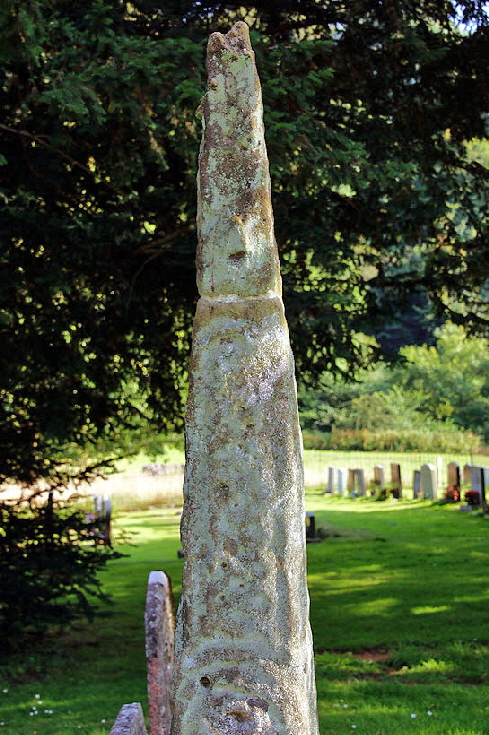

http://news.bbc.co.uk/local/stoke/hi/people_and_places/religion_and_ethics/newsid_8388000/8388209.stm. You must make up your own minds about how likely any of it to have been true. The font is Norman and attracts the familiar Pevsner epithet “barbarous” by which he meant crude. There are claims that the font is pre-Norman but this is far-fetched and the Church Guide is surely right in dating it between 1120-30. As Francis Bond commented as long as 1908 in his still indispensable “Fonts and Font Covers” “(some) sculptured fonts...have been credited with undue antiquity owing to the rudeness or uncouthness of their ornament; but it by no means follows that what is archaic is always ancient. This remark may apply to such fonts as those at Ilam...”. You don’t have to travel very far into neighbouring Derbyshire to find similarly crude carving on tympani as well as fonts - see “A Dawdle in Derbyshire”. What we are seeing here is undoubtedly the work of a village mason during the Norman period with little pretension to being a sculptor. Our native masons did not suddenly disappear or become multi-skilled craftsmen after the Conquest as innumerable examples on these pages attest. Bertram's tomb is also Norman but beyond these two furnishings there are no other signs of Norman work. The west tower and the east window are in Early English style. The east end dates from the Victorian rebuilding by the renowned Sir Gilbert Scott as does the unusual saddleback roof of the west tower. The tower itself, however, is genuine thirteenth century Early English with an impressively tall and narrow tower arch.. Even the most misguided Victorian Church Wrecker blanched at the thought of tackling towers! Scott also built the north arcade and commissioned many of the furnishings. The two Anglo-Saxon crosses are on the south side of the the church. They are weathered and battered, although some decoration is still visible. Most of the crosses on this site are in the Anglian style of the northern parts of England but Ilam is within the ancient kingdom of Mercia, not Northumbria, and Mercia was the last major English kingdom to convert to Christianity. Which is to say the royal house did at any rate! The crosses are likely to have been “preaching crosses” which would have served as a rallying point for early Christians to hear the Word of God from peripatetic monks. We don’t know why there are two but one or both presumably predated the building of the Anglo-Saxon church here. This is, nevertheless, a church largely of Gilbert Scott’s making, dominated by the Pike Watts monument on the north side. As a monument to the family I suppose it serves its purpose. It is, however, perhaps as much a monument to the extraordinary pretensions of wealthy families especially during the Victorian and to the fawning deference shown to them by the Church. I know I haven’t made a very good job of “selling” this church to you as a standalone attraction. It is, however, an attractive building in a gorgeous setting within a village of great beauty. The Pike Watts family created an attractive estate that includes Ilam Hall, very close to the church. The Hall and the estate is now owned by the National Trust and the hall is leased to the Youth Hostel Association!. If you love the English countryside then Ilam is a place for you and you should not ignore the church. Warts an’ all, it is worth a visit. |

|

||||||

|

The view from the west is perhaps the most attractive with the peaks rising up to form a lovely backdrop The church is a bit of a confusing sight with roofs everywhere and that rather odd saddleback roof. The mausoleum dominates the north side, dwarfing the aisle. What an act of hubris it was! The south chapel is far from lilliputian as well. The tower dates from the thirteenth century: few churches could contemplate the cost of replacing a tower. The west window is obviously later and by its factory-made look I imagine it is another Gilbert Scott-ism. |

||||||

|

|

|||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east end. The chancel arch arch, north arcade and east window are all Victorian and you have to remind yourself that you are in a church of Anglo-Saxon origins. Note the unusual low ironwork screen. Right: Looking west. The tower arch has the lofty height typical of an Early English tower. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

Left: More interlace work on the north side of the cross - with Ilam Hall in the background. Each component is hard to make out but the overall impression is of impressive geometrical complexity. Centre: Interlace work on the upper part of the south face. Right: The west face is badly weathered, |

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

The second of the crosses - further to the east than the other - is small at only four foot three inches. The cross, again, has gone but you can see its boss. A cylindrical base gives way to a square cross section that has some interesting chain-work carving on the south face, Weathering, again, has been unkind but you can still also vestiges of decoration on the east side and north side (right). It is a pretty little thing and the clarity of the carving on the south side is almost startling. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Norman font is crudely-carved by any standards. It is, mind you, also quite ambitious odd as that may seem at first sight. Ignore the central panels for now and look at the arcades that divide the font up. The sculptor has made them quite elaborate, his ambition outrunning his levels of skill. These are the sorts of columns that had been introduced into the arcade at Durham Cathedral a few decades earlier. Left: Two figures walk hand in hand. We haven’t much to go on but on a font your money would have to be on these two as representing Adam and Eve. Right: Instantly recognisable is that other old favourite the Agnus Dei despite its having been carved spectacularly badly. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Rather less conventionally, this monster has a man’s head sideways in his mouth. Right: A rather worried-looking chap, seemingly wringing his hands. The carver has deemed a neck to be superfluous, it seems. Note the columns on either side. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A single figure on one of the faces. Right: Oddly, the mason decided that one head-eating monster was not enough so this font has two! In this case it seems that the monster might have a human head beneath his forelegs as well. There are criss-cross patterns on the creature and they appear to be in red paint. There seem to be similar paint traces in the incised diamond design in the column to the creature’s right. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Top: The tomb of St Bertram lies beneath this thirteenth century altar tomb within the south chapel. Above: The view from the churchyard. This is a delightful place. Right: There are other tombs within the south chapel. This one is of alabaster and dates from the seventeenth century. The effigies are of Robert and Elizabeth Meverell of Throwley Hall s couple of miles away. Above the couple is the standing effigy of their daughter Elizabeth Cromwell. She sports a long black veil and - oddly - what looks like a coronet. To her right are her four children. If the name “Cromwell” piques your interest - as it did mine - you are astute. Elizabeth’s husband was Baron Thomas Cromwell and his descent was from Gregory Cromwell who was the son of the infamous (or maligned?) Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s henchman and subject of Hilary Mantel’s superb “Wolf Hall”. In 1537 Gregory married the widowed sister of Jane Seymour - the wife Henry is said to have truly loved - and thereby became Henry’s brother in law and uncle to Edward VI. Jane herself died in the same year. Gregory’s father fell in 1540 and was executed but despite Gregory’s close relationship with his father he managed to avoid being dragged down with him and became a wealthy landowner in his own right. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||