|

|

Alphabetical List

|

|

|

County List and Topics

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It’s time for another one of those pages that includes several churches that are interesting but not quite exciting enough to justify pages of their own. Diana and I spent a few days dawdling through Derbyshire. When we (okay, then when I!) draw up an itinerary I have to start somewhere and one of my starting points is always where I can find Norman fonts and tympana. I have to say, en passant, that I find that tympana as a plural of tympanum a bit odd. And it’s not helped by the existence of the word tympani which is an alternative spelling for timpani - a set of kettle drums. I hope that’s all clear and I have to extend my condolences to the billions of people around the world who are earnestly learning English as a foreign language. You see? We all struggle with it too sometimes.

So where was I? Oh yes. You are going to say see a lot of Norman fonts and tympanums (ha!) on this page because no church with one or the other is ever a boring church in my book. So enjoy this dawdle through Norman Derbyshire. It’s a very beautiful county with gorgeous scenery and lots to do and see besides churches.

Alsop

Poor old Alsop Church (St Michael) gets just five lines in Pevsner which must be some kind of record. So I’m putting it first! Actually, nobody has much to say about it and those that do shamelessly quote Pevsner. You know who you are! We know that the nave at least is Norman because the south door has what even Pevsner felt was a very unusual form of zig zag decoration. I would suggest that it is very late Norman. There are one or two original-looking Norman windows but their splayed embrasures are clearly not original. The chancel arch has Norman imposts but the pointed arch above it is clearly later. How much later is hard to work out but we know that the church was restored in 1882. The tower is, according to Pevsner, “faux Norman”. It certainly is, as is the tower arch, but it’s not clear whether there was anything here before. It’s hard to date the chancel with its modern rectangular windows. It has clearly been extended at some stage but it is not clear whether it was completely rebuilt or whether the west end of it, at least, is original Norman. Looking at it, I rather doubt it. Apart from the south door, my favourite thing is the Millennium window. It’s the sort of modern glass that I like very much. If all this sounds like damning with faint praise, then I apologise. This is a small piece of history in a quiet little corner of England. It is a tranquil place and that south doorway is actually quite charming. You won’t regret dropping in as you are passing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Top Left: The church from the south. Only the nave is definitely original Norman. Top Right: The lovely double zig zag of the south door. The rest of the doorway is plain but, oddly. this makes this little bit of decoration all the more charming in my eyes. Centre Left: The view to the chancel. Only the arch imposts are unequivocally Norman. The splayed window to the left is, I am sure, Norman but the splay has been restored. Centre Right: Looking West. The tower arch is Victorian. Despite all its alterations, Alsop still has the look and feel of a Norman church. Bottom Left: The little piscina is, I think we can confidently say, original. Bottom Centre: The lovely Millennium window at the east end is a true piece of art. It was designed and installed by Henry Haig in 2001 and represents Chapters 21 and 22 of the Book of Revelations - I’ll leave you to look up the words yourself. Bottom Right: A close up of part of the right hand panel. You can see that the designer has referred to Derbyshire’s industrial heritage and, as a boy from Birmingham, I really do applaud that.

|

|

|

|

Parwich

|

|

|

|

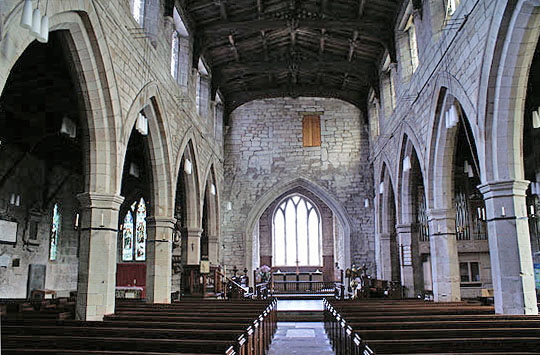

If you drove past Parwich Church you would probably dismiss it as just another Victorian pile. Then, if you went inside you might think at first glance that you’d got it completely wrong and that it was a Norman church within a Victorian shell. Sadly, your first impressions would have been right: this is a church that was completely rebuilt in 1873-4 replacing the original Norman church. That church was twelfth century and the Church Guide itself suggests that the Norman church would have looked much like the one at Ashover (above). Now, though, we have (not unattractive) faux Norman arcades, a rather elaborate and somewhat tasteless clerestory and a faux Early English east end. The tower is pretty awful to my eyes but you might disagree. I’ve seen much worse churches, though. What’s more, the builders retained some of the early features. The west door to the tower was the Norman south door. The tower arch is the original Norman chancel arch. The rather simple Norman font was also retained. Inset above the Norman door is a tympanum which is what drew me to this church in the first place. I’m going to take the liberty of reproducing the description from the village website because I can’t better it:

“The tympanum, which is thought to be of Saxon origin, is situated on the outside of the church above the west door, and is supported on two carved pillars of the same period. It was discovered under many layers of whitewash over the south door of the old Norman church before it was demolished. The stone is covered with rudely carved figures unfolding the story of the Redemption. On one side is a lamb bearing a circular-headed cross symbolising Christ as the Lamb of God; above the head of the lamb is a dove, typifying the Holy Ghost. The central figure is a hart, representing the Christian convert or true believer, and under the feet of the hart and lamb are two serpents with protruding tongues symbolic of the Evil One. Above is the swine into which the Unclean Spirit entered, and the remaining figure is a wolf, with tail expanded into a trifolium or shamrock. The latter is the emblem of the Trinity, and the wolf is represented devouring one of the leaves, symbolising the Denial of the Divinity of Christ”.

Now I don’t know who thinks it might be axon but I can’t see any reason for that assertion. It implies that the tympanum pre-dates the decidedly Norman doorway in which it is set. The pillars of the same (Saxon) period have beakhead moulding which is a decidedly Norman feature. a Saxon tympanum would also imply an Anglo-Saxon church and I just don’tt believe that such an out-of-the-way spot with no known monastic connections would have a stone built pre-Saxon church. I think crudeness in style is often used to falsely attribute church carvings to an earlier era but there are no grounds for thinking that new techniques and skills suddenly became available after the Conquest and there are a host of examples of very crude and indisputably Norman carvings on these pages.

Anyway, the tympanum is well worth a look and, damaged as it is, it is still possible to make out the details. For it alone, this church is well worth a visit.

|

|

|

|

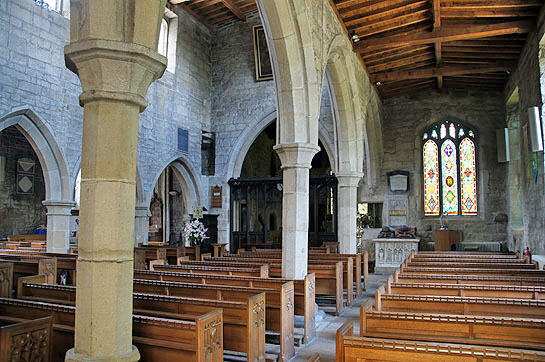

Ashover

|

|

|

|

Domesday Book proves that there was a church at Ashover in 1086 and there is even a list of rectors from that date. There is nothing left of that church, however, and today’s church was built between 1350 and 1419. Ashoverians will have to forgive me if I describe it as a “bog standard” church of the period. It is light and nicely proportioned, reflecting the zeitgeist of that Plague-ridden period. The treasure here, however, is the lead font that dates from around 1150, according to the Church Guide, 1200 if you believe Nicklaus Pevsner who was also a little disparaging about its quality. England was Europe’s largest lead producer at the time and lead was mined in this part of Derbyshire. Many were melted down for bullets in the English Civil War but this is one of twenty-nine survivors in England. The churchwardens had taken the precaution of burying it! Unusually, the bowl is of stone with the lead wrapped around it. The method was to cast it flat and then to curve it while hot, and then to solder the join(s). It’s an odd affair. Twenty figures stand within typical Norman-style arcading. Twenty. So not apostles then? So who were they? Well, here’s the oddity: there are apparently two figures represented ten times. I say “apparently” because although there are two different postures, I don’t think that any two figures are precisely the same. Now, I’m thinking out loud here but why would that be the case? You would have thought that the manufacturers would have used some kind of die and or stamp and that they would have had just two that they used again and again. I say “you would have thought” because I can’t find anyone who thinks they do know how lead fonts were made! Anyway, assuming they were just representations of two men then who were they? I thought SS Peter and Paul. But Paul without his keys? I don’t think so. Each seems to be carrying a book. Paul was often this represented in reference to his “Letters”. Is each figure supposed to be him? Hmmm.

There is also a fine alabaster monument of 1511 to Thomas Babington and his wife Edith. This, presumably, is the reason for the one star awarded by the monument-obsessed Simon Jenkins! An earlier Thomas Babington actually commissioned the building of the church. In 1586 one Anthony Babington, was executed for his involvement in the Babington Plot to kill Queen Elizabeth I and replace her with the Roman Catholic Mary Queen of Scots. Apparently the executions of Babington and six of his co-conspirators were so ghastly that even the normally case-hardened Elizabethan mob was revolted. The sentence read (don’t read it if you are squeamish!): "From (the Tower of London) you shall be drawn on a hurdle through the open streets to the place of execution, there to be hanged and cut down alive, and your body shall be opened, your heart and bowels plucked out, and your privy members cut off and thrown into the fire before your eyes. Then your head to be stricken off from your body, and your body shall be divided into 4 quarters, to be disposed of at (the Queen's) pleasure. And may God have mercy on your soul." Such was the public reaction that the last seven conspirators were hanged to death before the mutilations took place. Bear in mind, if you are not already feeling a bit nauseous, that the executions happened one by one. Babington was second to be put to death so he would have watched what was done to the first victim. By the time the last unfortunate was dealt with you would have thought he would have been out of his mind with terror.

|

|

|

|

Hognaston Church is like so many I am decribing on this page; of Norman origin but rebuilt by the Victorians in 1879-81. As with Parwich, it is a Norman doorway and tympanum that brought me here. The naivety of the tympanum carving and the clasping beakheads on the doorway pillars are both very reminiscent of Parwich.

The tower is thirteenth century apart from the top stage which is Perpendicular in style. The rest of the church is another example of Victorian eccentricity. It has pseudo-Norman arches and capitals mixed in with Gothic style windows that make no connection with traditional patterns. Parwich, I must say, is a much more satisfying composition.

Anyway, it’s that south doorway - presumably in its original position - that we’ve come to see. I am going to quote Pevsner: “Amazing Norman doorway. The tympanum shows incised pictures of a bishop with a crook, the lamb with cross, two fishes, a hog (?), and several other beasts. What on earth did our forebears mean by such representations? And how can one account for this total lack of sense of composition and this utterly childish treatment?” Phew. Come on, Nicklas, stop mincing your words! Another person on the internet has suggested it must have been the work of the village blacksmith! Well, as I said in the context of Parwich, the ability to reproduce zig zag moulding and to hew stone blocks does not imply any artistic talent and I am sure that this is a case of some mason just doing his best. Nobody seems to have essayed much on the way of interpretation but I did unearth this quote from one Mrs Jameson in 1913. “When wild beasts as wolves and bears are placed at the feet of a saint attired as abbot or bishop, it signifies the cleared waste land, cut down forests and substituted Christian culture and civilisation for Paganism and the lawless hunter’s life...Even when as at Parwich, there is no ecclesiastic, the symbolism may be much the same”. That sounds as good an explanation as any to me.

|

|

|

|

Left: The church looking towards the east end. The Victorian windows are rather peculiar and aesthetically a bit dubious. Right: The view to the west end. It’s not an unpleasant space to be in but it’s a total mess architecturally. There are faux Norman columns and capitals supporting pointed gothic-style arches and they have been filled by glass. It makes for a strange mixture but I am sure the glazed arcade has enabled much more economical use of space and it’s not for me to demand that architectural aesthetics are put above the practicalities of a functioning parish church. Its important that our churches are used.

|

|

|

|

Tissington Church sits in a picture-postcard village opposite Tissington Hall and just yards from the well which is dressed with flowers every year in that ancient and much-loved Derbyshire tradition. The church too has somewhat superior, almost complacent, air about it. Of the churches on this page there is no doubt which attracts the most visitors and it’s almost as if the church knows it! Sadly, however, its Victorian restoration was ruthless and left a charmless Norman pastiche. There is a Norman tympanum here which manages the near-impossible by being even cruder than those at Parwich and Hognaston and moreover without any recognisable story to tell. It is the Norman font, however, that is the star of the show. Unsurprisingly, however, the ambition of its creator far outran his skills and so it is another example of the Derbyshire Kindergarten School of Norman carving! Nevertheless, the imagery is transparent in its meaning a thousand years later and that is not to be sneezed at. The Norman chancel arch also survives but even this has lost its left side to the over-bearing and ugly monument to Sir John Fitzherbert of 1641. The base of the Norman tower survives as you must now have come to expect.

The tympanum is a peculiar affair. It has a kind of chequerboard pattern and in the middle of it half a dozen billet-moulding squares form a cross. Either side of this are two grinning figures, arms akimbo as if to say “well we haven’t seen you in here for a long time!”. It is irredeemably crude; the work clearly of a man who was as devoid of ideas as he was of artistic skill. If you are a student of Norman carvings, however, it is quite compelling as a reminder that the Conquest did not produce some kind of national artistic renaissance. In the remote corners of England, away from the guidance of monks and abbeys, simple men of Anglo-Saxon origins were struggling to follow the new fashions and just doing their not very talented best. The church wanted a carved tympanum. This man, who probably just built walls for a living, gave them a carved tympanum. He did his best and he probably got his leg pulled about it by his mates. I don’t suppose there was a queue of volunteers. These tympanums might not be art but they are culture and they are history. And the laugh’s on us. How many of us will leave something that people will be talking about a thousand years later?

The font is not terribly easy to make out from the photographs. The design is incised rather than carved. There is an agnus dei which is marginally more ovine than those at Parwich and Hognaston. There are two beasts and two human figures. One of them beasts has a man’s head between its vicious-looking teeth and also has a tail curved around its body. The other may or may not be taking a bite at his own tail. The Church Guide suggests that these are bestiary figures although it further admits that this was not common on fonts. I am always deeply dubious about claims to bestiary origins because that suggests access and the ability to read such a book. I think we’d all agree that there is little sign of monastic influence on the carvings in this area so that if a bestiary was indeed the original source this carver would have acquired his knowledge by copying work elsewhere or via some kind of oral tradition. There is also a bird shown and the Church Guide suggests it is possibly either the eagle of St John or or the dove of the Holy Spirit. Another possibility is that Christ was often called the “sacred bird”.

|

|

|

|

Left and Right: The external church is a bit of a mess really! Note the clutter of windows in all manner of styles on the south side including a particularly jarring rectangular window at the south west corner. The chancel is a little tidier with faux (and oversized) Norman-style windows to each side. The north side is quite different. Here the “Normanisation” is total with faux Norman windows throughout the length of the north aisle and with mini-Norman style lights to the clerestory. This is, however, a well-kept north side. Many churches seem to despise the north sides no less than did their mediaveal parishioners! In size the church is rather grand, befitting its proximity to the Hall. I’m afraid the restorers did it no favours though.

|

|

|

|

Left: The west tower still has its Norman base. Right: The road sweeps from the church past the hall on the left towards the village beyond. Just before the cars on the right is the well which is “dressed” with flowers during the Summer. If you don’t know about Derbyshire well dressing then follow this link : http://www.visitpeakdistrict.com/events/Well_Dressing.aspx. I’ve added a few pictures from various places in Derbyshire from 2016 in the footnote below.

|

|

|

|

Repton

|

|

|

|

If Tissington is the most-visited of the churches on this page, the Repton is certainly the most famous. Simon Jenkins gives it three stars. I am afraid my pictures do not do justice to it, so you will have to forgive me. This church is not in the rural Peak District of Derbyshire and its main point of interest - its crypt - is not Norman but Anglo-Saxon.

In Anglo-Saxon times, Repton, then known as “Hrypadun”, was a Very Important Place. It probably belonged to a monastic house for men and women that was built in the second half of the seventh century. Mercia was perhaps the most reluctant of the Angle-ish kingdoms to “convert” but in AD653 King Peada and some of his family were baptised here. Repton was the centre of Mercian Christianity until King Offa got tired of seeing Mercian bishops paying allegiance to the see of Canterbury and founded his own at Lichfield. Repton’s importance did not disappear, however. Its eighth century crypt which you can still visit was the burial place of the Mercian royal house. St Guthlac was a monk here until AD699 before founding the monastery at Croyland in the Cambridgeshire Fens,. The murdered King Ethelbald was buried here in AD757. The town of Repton has the distinction of being the only positively identified location of a Viking over-wintering site in AD 873-4. The monastery wa demolished by the Vikings and since there are no subsequent records of it, it seems it was never rebuilt.

The chancel here is almost the original Anglo-Saxon one. It is extremely shallow, rather in the style of Escomb in County Durham, and has characteristic pilaster strips to either side. West of the chancel there was originally a square central space that had transepts. Part of the north transept is now built into the north aisle. You can still see the Anglo-Saxon masonry on the chancel wall. The nave is mediaeval. It is fine enough in its own way but if you come here it will be to sample the extraordinary air of sanctity of the crypt.

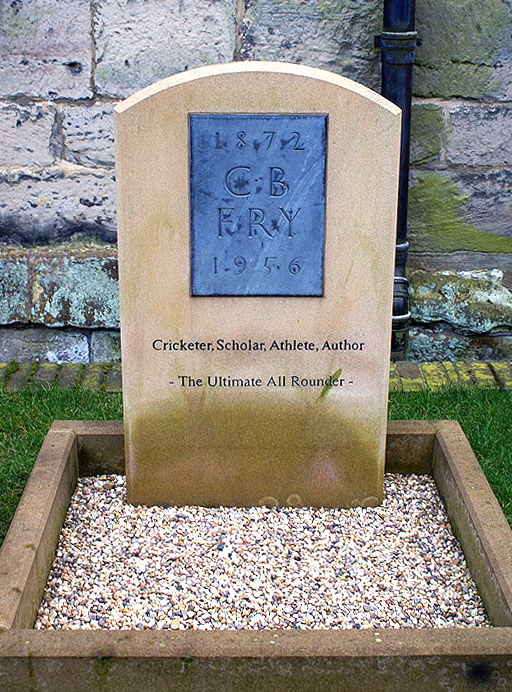

Finally, Repton is also the location of the famous public school. Next to the church is the burial place of its most famous son - one Charles Burgess Fry (1872-1956) who is legendary as the first man to represent England at both football and cricket. That’s as well as holding the British record and equalling the world record at Long Jump. He was also a talented high jumper, sprinter, and ice skater. He played rugby for Blackheath (then one of England’s most illustrious clubs) and the Barbarians. When I was a lad, I used to love the “Wizard” and “Hotspur” comics (they have i-Pads these days) and there was a wonder-athlete character named “Wilson” who first appeared in 1943 (before my time, I hasten to add). His incredible achievements included, amongst other things, the first three minute mile. It was widely believed that he was based on C.B.Fry but I am surprised to find no references to that now on the internet.

|

|

|

|

Left: The church from the south. This is a very large church with a very lofty tower. Centre: The north side of the narrow chancel with Anglo-Saxon pilasters. I suspect the “transepts” were similarly shallow - more like porticuses than the transepts of the mediaeval period. The walls of the chancel are believed to represent three stages of building. although even the topmost and most recent is believed to be ninth century. Note the small doorway barely visible at the foot of the wall. It may well be that originally the crypt was accessible only to royalty and dignitaries and there was no access to the crypt for the commoners in the main church. That probably changed when Wystan, to whom this church is dedicated, was made a saint. Wystan was chosen as king in AD840 but asked his mother, Elfleda, to rule in his stead. His cousin, Berhtric, proposed to marry Elfleda in order to grab the throne for himself. Wystan opposed the marriage, declaring it incestuous, at which point Berhtric murdered him probably at Wistow in modern Leicestershire. Wystan was buried at Repton and it became a place of pilgrimage and it is probably at this point that stairs were built from the church transepts into the crypt. On the other sides of the chancel are recesses that may have housed shrines or tombs. Right: The crypt. It has nine small chambers in a space sixteen feet square and the whole lot is supported on four huge columns of which you can see three in this picture. They are designed for durability rather than for decoration.

|

|

|

|

I arrived at Ault Hucknall on a Summer’s Sunday afternoon to find it locked, which was disappointing. I’d mainly come here to see its outside, however, so I managed to cope with it! As with many of the churches on this page its origins are Norman and its decoration crude - “highly barbaric” Pevsner called it, using one of his favourite words with his customary relish. The church has a central tower and a crossing that Pevsner was tempted to believe could be Anglo-Saxon but nevertheless, as he acknowledged, it is Norman. The Norman core is, as in so many English parish churches, hidden behind embattled Gothic aisles, porches and clerestories.

It is the tympanum and the lintel on the west end over the filled-in west door that is the great treasure here and what led me to this quiet part of the Derbyshire countryside. The tympanum itself is typical of the area, both in it subject matter and in its crude execution. As usual you can quibble over what it is meant to be but an Agnus Dei is the most plausible explanation for the figure to the left, and that on the right seems indisputably to be a Centaur but in this case it is not just any old centaur, but Chiron. Chiron was a rather superior version of the centaur with qualities in healing, medicine, hunting and prophesying that were similar to those of Apollo. He was often represented with human rather than equine forelegs rather but this nicety clearly eluded the mason at Ault. We know it is Chiron, however, because he is waving a handful of ‘erbs.

It is the lintel that is of most interest here, however. Pevsner speculated that St George was fighting the Dragon. If you have been reading a lot of my pages, however, you will know of my reverence for the work of the late Mary Curtis Webb. She identified the figure as Christ, not as St George or St Michael, and he is fighting the Devil in the guise of Leviathan, not a dragon. Admirably, and unusually, this church has recognised Mary Webb’s research on their display boards.

The Christ figure is clearly in the form of a Norman soldier of the day - his kite-shaped shield is the dead giveaway. Note that he is not wielding a lance, such as you would associate with George and Mike, but a knife. Echoing Pope Gregory the Great’s famous commentary on the Book of Job - the “Moralia” - Christ is going to use the knife to cut the flesh of Leviathan to pieces. To Christ’s left is the shackle with which Leviathan had vainly hoped to shackle Him. A cross is inserted between the two figures. Leviathan is a particularly fun figure here, although one imagines that this was unintentional. Our mason had next to no skill in the art of sculpture and would presumably known nothing of Gregory’s “Moralia in Job” so we have to assume that he was directed by a denizen of a nearby monastery. We must assume that it was from the same source that he learnt about Chiron.

|

|

|

|

Left: The church from the south west, with the tympanum visible on the west wall. Behind that Gothic carapace is a Norman nave and you can just see that the north aisle with its very steep roof pitch and its tiny window is also Norman. Right: The tympanum. Chiron is to the left waving his herbs, and probably Agnus Dei is to the right. It is badly weathered but that round cross behind the animal is one of the usual signs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above: The lintel with Christ in the guise of a Norman soldier fighting the Devil in the form of Leviathan. A cross separates them.

Top Left: A close up of the Christ figure. It is remarkably naive. Note the kite-shaped Norman shield. Behind Christ is the shackle with which Leviathan intended to bind Christ. It is very much an Old Testament representation of the struggle between Christ and the Devil.

Top Right: Leviathan pokes out his wonderfully forked tongue. Note the large curl of his tail which is characteristic of the carved Leviathan figures in England. See particularly the one at St Bees in Cumbria.

Left: This is the north west aisle window. It is very obviously Norman and quite unsophisticated with its incised zig zag pattern.It is hard to believe this was its original position. Note the enormous stones that flank it. Pevsner put the original church at eleventh century which seems very plausible. What, though, is the curious decorated stone to its right?

|

|

|

|

|

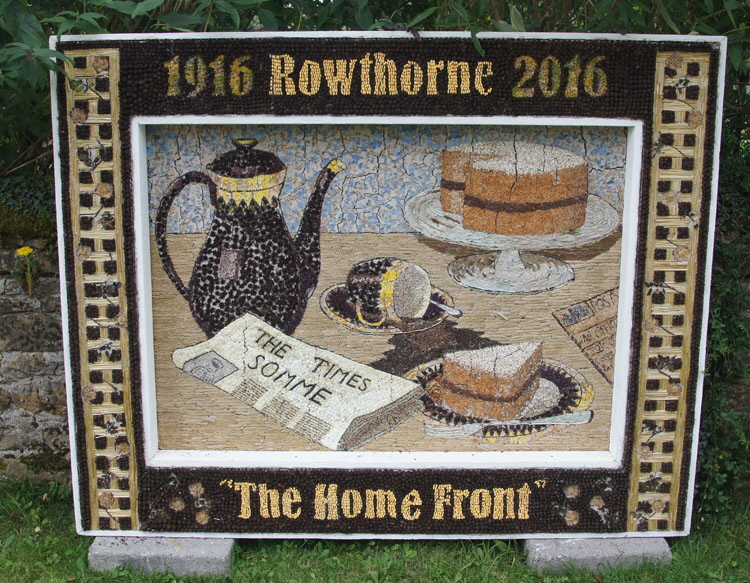

Footnote - Derbyshire Well Dressing

|

|

|

|

There are plenty of websites that can explain this ancient and picturesque practice much better than I, so I will confine myself to a few pictures taken in 2016 for the benefit of overseas readers for whom it might be a mystery. All of the designs are made solely with flowers and vegetable material. After a while it is normal for some of the plants to begin to sprout through!

|

|