|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

feeling of airiness and lightness. This was a church built on the proceeds of tin mining and perhaps the miners already spent enough of their time in gloomy surroundings. There are timber roof supports throughout the church and the intersections of the timbers are many wooden bosses, some very interesting and all colourfully painted. The most celebrated is the “triple hare” symbol. The Three Hares symbol is popular in the West Country and appears on several churches in the area. It is sometimes known as the “Tinners Rabbits” in this area but really no name could be further from the reality: the Three Hares symbols is at least 1500 years old and is found in many cultures and religions throughout the world - and nobody can say definitively what it means. They have been found in seventh century cave paintings in China and in thirteenth century metalwork from Iran, then part of the the Mongol Empire. It is found in Buddhist and Hindu contexts as well as with Christianity. It is suggested that the symbol reached the West via the Silk Road. In Christianity it is seen as a symbol of the Trinity and, let’s be honest, that’s a pretty universal and maybe lazy interpretation of anything that appears in a church in a group of three! Certainly, nobody can be certain why the West Country favours it so much and nor can anyone explain why it is so often found next to or close to a Green Man symbol - as it is here at Widecombe. The Green Man himself, universal as he is, is not definitively understood. Widely seen as a pagan symbol, revisionists have tried desperately and unconvincingly to find a Christian meaning. |

|

|

||||||||||

|

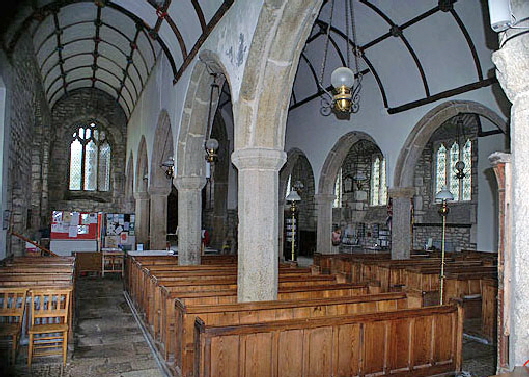

Left: The view to the east of the church. The arcades are wide, the windows large, the ceilings whitewashed. This is a light church (although it was gloomy on the wet early evening that we visited!). Right: The north aisle. You can see that both aisles are very narrow. See how few seats are gained - although of course when the church was built the congregation would have stood. I think that only in the West Country would aisles have been built so narrow in the fifteenth century. Indeed, there was a massive program of aisle enlargement throughout the rest of the country at the time Widecombe was built. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The church has small transepts on eother side. This is the south transept. The perpendicular style window is original. Note that the arch is made of timber but supported, of course, by stone blocks. Note that the waggon roof and accompanying bosses continue even into this small space. Centre: The surviving doorway to the rood loft with the stair opening above it in the north aisle. I wonder, by the by, why rood lofts were invariably placed on the north sides of churches? You can see the surviving dado part of the screen next to the doorway. Right: A peculiar arrangement of three stone crosses displayed within the church. They are believed to have fallen from the tower during the lightning strike and may have topped the pinnacles of the tower. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

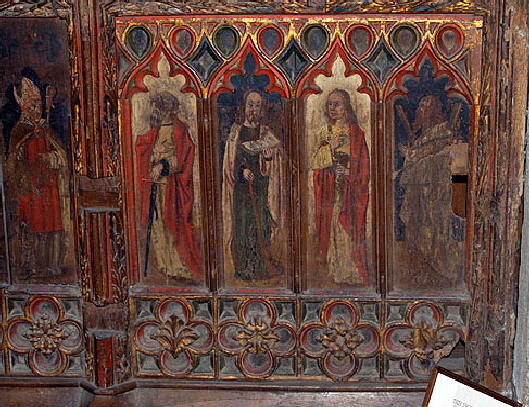

Two fragments of the rood screen. Because of the West Country tradition of continuing the aisles alongside the chancel as well as the the nave, this would have been a very wide screen. These two pictures show only about a third of what survives. The pictures are of the usual collection of apostles and saints and there has been some defacement, probably when the rood itself was removed after the Reformation. On the far right of the right hand picture St Andrew with his saltire cross is clearly visible. The whole thing looks ripe for restoration, although I suppose some would argue that it is better to be able to see what was original. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The “Tinners Rabbits” boss. Anatomically, they do look more like the hares that they are meant to be! Note that there are only three ears to be seen. This sharing of the ears is an integral part of the three hares symbol throughout the world. Right: One of the ubiquitous Green Man figures that so divide opinion! |

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Left: An awful lot of mediaeval carving in both stone and wood is loosely attributed to the “bestiaries” of the period: I say loosely because the mason or carpenter was invariably ignorant of what the animals actually looked like! This one, however, is almost certainly an Ibex because it really looks like one and the carver would have been fully aware of the physiognomy of the domestic goat which also appears in the Bestiary. I quote here from the English Bestiary from the Bodleian Library: “there is an animal called the Ibex. This creature has two horns which are so strong that if it falls from a high mountain down a precipice, its horns bear the whole weight of its body and it escapes unhurt. This beast represents those learned men who understand the harmony of the Old and New Testaments so if anything untoward happens to them they are supported as if on two horns by all the good they have derived from reading the witness of the Old Testament and the Gospels”. So now you know! Second Left: This is less obvious but most likely, I surmise, to be an eagle. The Bestiary entry is long so I won’t reproduce it but you might be amused at the first line: “the eagle is so-called because it is eagle-eyed...” which is an interesting piece of inverted logic! Anyway, the entry goes on to recount that “when it grows old its wings grow heavy and its eyes cloud over. Then it seeks out a fountain and flies up into the atmosphere of the sun; there its wings catch fire and the darkness of its eyes is burnt away in the sun’s rays. It falls into the fountain and dives three times: at once its wings are restored to their full strength and its to their former glory”. The lesson is that by turning your mind to the “spiritual fountain of the Lord and lifting the eyes of your mind to God you will renew your wings like the eagle”. Second Right: This is much less obscure: St Catherine with her wheel. Her hair is unbound because she was unmarried at her death and she wears a crown because she was a princess. I her right hand she carries the sword with she was finally killed. Far Right: We can only speculate at the the identity of this hirsute individual! |

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

Left and Centre: There are two images of the Pelican in her Piety. This may be because of the reconstruction of the nave roof after the Great Storm.. The Pelican is perhaps the most common bestiary image in English churches. The belief was that the pelican’s offspring would strike the parents in the face when they grew and that the parents would retaliate and kill the children. After three days the mother would then peck her own breast, lie on her young and pour blood upon their bodies whereupon they would revive as a result of her love. The allegory, of course, is that we sinners are the offspring and the pelican is Christ who loves us and revives us with his own suffering. Right: The church has a St Catherine’s Chapel at the east end of its south aisle. This original altar stone was found buried in the floor of the church and is now restored to its original position. |

|

Footnote 1 - “Widdecombe Fair” |

|||

|

I learnt this song at primary school and I think most of my generation did. I am not going to make the mistake of assuming that successive generations also did but the use of the words “Old Uncle Tom Cobley and all” is still widely used as a metaphor for “everybody”. It is a folk song and recounts the story of a “grey mare” lent by Tom Pearce to a group travelling to Widdecombe Fair. The horse dies. It is one of those many folk songs that takes a lot of verses to recount very little but where the joy is in belting out a catchy chorus over and over. It was first published in Sabine Baring-Gould’s “Songs and Ballads of the West” in around 1890. Diana has particular interest in the extraordinary Sabine Baring-Gould whom you can read about in my page on Lewtrenchard. |

|||

|

|

Footnote 2 - Mediaeval Bestiaries |

|

Right, so this is not a straightforward topic. Nothing much concerned with religion ever is! The first premise of the Bestiary is that every beast was created with an ulterior motive of teaching morality to sinful man. It was a constant theme amongst the earliest Christian fathers that really mankind was a pretty awful piece of work, horribly and eternally tainted by that dreadful Adam who had fallen into temptation and copulated with Eve. Actually, as that breathtaking masochist St Augustine of Hippo had propounded, the real sin was to have enjoyed it. Sex, Augustine, had argued, should have been a pleasure-less mechanical act of procreation and Adam had spoiled it for everyone. Christianity has had a pretty severe view of sex for the best part of two thousand years. In fact, when you read early texts, it was a major preoccupation. It’s not hard to see why. Human beings might conceivably be able to resist stealing, murder, the worship of graven images and even of coveting one’s neighbour’s ass; but who never feels sexual desire? So it was a pretty convenient peg on which to hang the hat of “You are all sinners and, therefore damned”. Augustine reckoned that Adam’s sin was transmitted from generation to generation via sperm. Thus it is only recently, in historical terms, that the Roman Catholic church abandoned its doctrine that even a baby, if unbaptised, was bound for hell. So the beasts of the field, real and imagined, were there as morality tales for us all. The Greeks did their bit, describing the various behaviours in pretty fantastical fashion but it was the Christians who really got stuck into it all. It started with a work called the “Physiologus” written sometime between the second and fifth centuries AD. It was written in Greek in the Egyptian city of Alexandria. Alexandria was a centre for Christian theology. In the unedifying politics of Christianity at that time, Alexandria, Rome and Constantinople were constantly at odds over theological doctrine. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) was himself its bishop at one time and the leading light in its school of Christian thought. Bizarrely then, you may feel, while the Christian fathers were arguing the toss with each other about weighty philosophical matters such the nature of the Trinity and whether God and Christ were one, two or the same beings, somebody else was writing the Physiologus in which the behaviours of birds and beasts were translated into morality stories for Christians. Sometimes these stories were reinforced by scriptural references but the authors must have been maddened by the fact that these references were far from consistent so some animals had both Christian and diabolical significance; and these had to be reflected in the bestiaries. This being the time before Easy Jet and Ryanair, the author knew little about their real behaviour or even what they looked like. Indeed, the behaviours were described much as the Greeks had described them centuries before. The Physiologus, nevertheless, was a runaway success. From that work all future bestiaries emerged. One bestiary would use another as its basis and might add a few local folk stories and legends of its own but fundamentally they all trace back to the Physiologus. The one I quote from here is a synthesis of two documents of between 1220 and 1250. Bestiaries were widely translated and nearly all had already been translated from Greek into Latin so the documents were likely to be unreliable, to say the least. We can see in Widecombe Church that the Bestiary was still in allegorical usage in the fifteenth century. The Pelican in her Piety is widely used in churches and is an especially popular theme for misericords. The Bestiary has informed masons and carvers, it seems, throughout the second millennium and perhaps before. When confronted with a mass of indecipherable carving at a church, however - especially a Norman church - some people like to airily proclaim “of course it would all have come from the Bestiary”. I am a sceptical about this claim. Books were extraordinarily rare and precious objects pre-Caxton and it passes belief that ordinary church masons would have had access to them. Some suggest that the masons would have been informed by educated monks and that was surely sometimes true. That might account for the pelican’s popularity on misericords: misericords were the furnishings of monastic churches. Very few images on ordinary parish churches can be definitely identified with the Bestiary, however, beyond the everyday images of, for example, lions, eagles and dragons. I suspect that the Bestiary was rather less influential in church carving than is generally supposed. There is a constant theme in mediaeval church studies: the concept that imagery we find indecipherable today would have been instantly recognisable and would have had meaning to the illiterate mediaeval peasant. I even possess a splendid book of Romanesque imagery that is called “The Villeins Bible”. Really? I can buy the fact that the Last Supper around a font, the imagery of Adam & Eve and the Tree of Life, Christ’s baptism to mention but a few would indeed be recognisable to the the church-going “villeins”. Wall paintings of the Last Judgement, St Christoper, the martyrdoms of Catherine and Edmund - I can buy those too. Our villeins would surely have been aware of those stories. Many of the others I see are, however, obscure even to today’s scholars. Mary Curtis Webb’s findings about the basis in Platonic philosophy of some Norman font carvings prove the point that some carvings were only decipherable to the educated tiny minority - surely by design. My endless exploration of churches and especially their carvings convinces me that if a carving looks obscure then it probably was just as obscure to the common man when it was carved! Should we really be surprised? Today many of us would say that a lot of art speaks only to other artists and to critics. Artists like Jack Vettriano speak to ordinary people and he’s justifiably proud of it. So what of our Widecombe ibex? Did the tin miner know it was an ibex and, if he did, did he know what lesson he was to draw from it? You know, I doubt it very much! At that height and without spectacles he probably wouldn’t even have been able to see it!

|

|

|