|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

Dedication : St Helen Simon Jenkins: Excluded Principal Features : Door of National Importance; Magnificent South Doorway |

|

|

|

|

we seen now was part of a major restoration of 1877. The ornate south doorway and an abundance of surviving decorative string coursing speaks of an ambitious decorative scheme for such a small church. As we shall see, the south doorway decoration is full of sophisticated symbolism so we must assume monastic input here even if Robert de Stutville was still the patron. The tall lancet window in the lowest portion of the tower tell us that it was probably early thirteenth century. This period also saw the addition of a north aisle and chapel of respectively two and one bay. The Norman north door - itself not lacking in vigorous decoration - was reset into the aisle. A chantry chapel dedicated to St Mary was added by Nicholas of Moreby in about 1336. Interestingly the capitals of the two bays are decorated with fabulous beasts (and now you know “where to find them....”) marking the first shoots of a revival in figurative carving as part of the Decorated style following the hard-to-explain decline in the Transitional and Early English periods. In 1520 the presumably Norman chancel arch was removed. and the tower received its third stage. New windows were also installed in the north aisle. |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: The magnificent south door with five orders of decoration. Right Upper: Of the five orders, the innermost course of figurative carving is the most interesting. Then comes two courses of chevron moulding, the outer of the two being enhanced by another decorative design. Then we have a course of the iconic beakhead moulding and on the outside a course of palmette decoration. Right Lower: We are fortunate indeed that there is still a lot of crispness to the designs. Remember these have survived nearly nine hundred years of exposure to all the Yorkshire weather and two hundred years of industrialisation can throw at them. The voussoir on the left is identifiable as a Tree of Life design found on other Yorkshire doorways at Riccall, Barton-le-Street and Fishlake. To the right is a fabulous beast with foliage emanating from his mouth - at least I think it’s foliage. Rita Wood in her splendid work “Paradise” (2017, Theophilus Publishing) suggests that most south door symbolism is related to man’s entry to Paradise. She sees foliage-emitting beasts and men as a symbol of God’s gift of a new life in Paradise. This is a different take altogether on the Green Man that is so often seen as a pagan symbol of fertility. By the way, Paradise is not Heaven. Paradise is the place where the righteous would wait for the Second Coming and Judgment: a sort of waiting room for the worthy. I will return to the south door later. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: The historic south door which is now protected by a new outer door. Of course, it is not easy to photograph in this position! Right Upper: The top half of the door. Adam and Ever are top left. The C-hinges have dragons’ heads at their extremities. The Viking longship is clearly visible. Other fragments are frustrating testimony to the parts that have been lost. The incomplete circle of nails near Adam and Eve’s heads are likely to have held the image of a tree of knowledge. Right Lower: A piece of complex interlaced iron strap work separates the two halves of the doorway. The lower hinges also have dragon heads. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The longship. Right: This is an interesting motif. Is it “just decorative” or does it have some sort of symbolic significance? Within the context of a door that seems to have been anything but “just decorative” I think it does. See the footnote below. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Adam and Eve figures. It is a delightful piece of decorative work and quite moving. Eve on the left has tiny “breasts” to identify her while Adam reaches for the apple from a now-disappeared tree egged on, it seems, by Eve. Right: Detail of the decorative central band. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This is the reverse of the south door showing the way it has been patched up over the centuries. Centre: The north door is also Norman, It too will have been moved when it was displaced by an aisle. The higgledy-piggledy nature of the voussoir perhaps bear witness to that. Note also the awkward geometry of the lower hinge. Right: The replacement south door and the inner decorative course of the doorway. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Sometimes my determination to avoid using flash photography in churches - the right policy 99% of the time - rebounds on me; hence this fuzzy picture on a dull late afternoon in November! This is the church looking towards the east. The arcades and the loss of the original Norman chancel arch give the church an undistinguished look that belies the importance of its south doorway. Right: The chancel with an archway to the north chapel on the left. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west. This is a church that, to its great credit, is proud of its history and provides plenty of story boards for visitors. Centre: The north aisle looking west. It is a narrow aisle with a steep roof exactly as you would expect with an aisle as early as this one that has not been enlarged. Right: The effigy of (probably) Robert de Moreby (d,1337). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south aisle. The three capitals of the arcade have figurative carvings. This is yet another example of figurative carving starting to re-emerge in parish church architecture after its hiatus during the Transitional and Early English periods. The mood, however, has changed. The carvings are more robust and what seem to be pagan or folk themes perhaps reflect the loss of monastic influence and the new assertiveness of the stonemasons. Right: The “Saracen in Submission” motif. This is a rare piece that shows a “Saracen” - seemingly a catch-all description of any contemporary Muslim - bound and subdued. The costume - note especially the pantaloons! - is of interest. So too is the historical context. By this time the Crusades were finished and the “Saracens” had not “submitted” at all. In 1291 the formidable and ruthless Baibars, ruler of the Mamelukes, had ousted the Crusaders from their last stronghold at Acre in modern-day Turkey. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The south aisle capitals - apart from the “Saracen” - have not worn well over the centuries and there have been somewhat clumsy efforts to patch them up. There are a couple of “green men” and “populated” foliage with robust and assertive faces seem to have become very fashionable in churches great and small during the period of the Decorated style. This really was the heyday of the Green Man. I wonder if anyone knows why? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The south door capitals. I am not going to attempt to describe these in detail but all seem to heads. On the carving on the left you have to look quite hard to see a “cat mask” hiding facing horizontally on the right side. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Let’s turn back to the figurative carving on the south doorway. Left: A flower design to the left, its tendrils leaking into the soffit. To its right is a lion with a tail that is foliage. Right: We have a mask with a lion in front of but not apparently inside its mouth. Then there is a beakhead carving. To the right is a man’s head with a crown (?) of three crosses. Rita Wood suggests that this latter carving represents Christ ascended to Heaven. There is an awkwardness about the positioning of the three voussoirs that suggests the re-siting of the doorway was not with out its challenges! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: These two designs are nicely preserved. To the left is a complicated design. An eagle with accurately-portrayed talons and beak is joined to a hound by what is presumably a piece of rope. It loops around th body of the eagle and the neck of the hound. Less easy to see is a third animal with a long tail on the underside of the carving. Right: Two masks emit foliage that joins together and forms a knot design. Right: A peculiar design of two masks facing each other and sandwiching two mens’ heads. To its right is what appears to be another foliate design. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another mask is spewing a lion from his mouth. Centre: This is the carving that excited me most. It is another of the “circle interlaced with arcs” design as described and explained by Mary Curtis Webb. This one is unusual in that it has a cross running through it. It is almost identical to a voussoir of the ruined Reading Abbey that dates from about 1140. Reading Abbey was, according to Mary Webb, the intellectual wellspring for the Platonist carvings found in the Buckinghamshire area. A slight peculiarity is that the device is not precisely aligned along the cardinal points. You can see quite clearly that this is not a quirk of the alignment of the stone itself. Right: This looks like it was originally a Norman window at the junction of the nave and chancel on the south side. It looks like it was turned into a nice for a statue. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Let’s have a look at the outermost course of decoration. It is a very curious set of designs. They are mainly stylised and most are in the form of two U-shapes of different sizes. Most are filled by a foliage design. You can see, however, that a circular flower design breaks the pattern and it is very similar to a design in the innermost course of decoration. That is most peculiar. Right: One of the stones has a human head. Just for the hell of it, it seems! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A section of the beakhead course. What a mystery beakhead is! You will find it all over the surviving Norman churches in England but it dates only from around 1130 and was pretty well passe by 1370. It looks Scandinavian seventy years after the Norman Conquest - an Anglo-Scandinavian design more than anything else. Yet nobody knows what it means. Right: This pretty round window with a trefoil insert is in the south aisle. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Amongst the Romanesque joys of this church are long lengths of decorative string coursing. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel from the south. The little window to the left has been filled been used as a niche (above). With wearisome predictability the little Church Guide describes it as “leper squint”. If you want to know why that is nonsense then you’ll have to look elsewhere on this site because I’m fed up with talking about it! The grimly utilitarian windows and priests door as part of the appropriately-named Fowler’s “restoration” of 1877. I suppose we should be grateful he didn’t demolish the wall completely to get rid of the un-Victorian string courses. Right: The view form the north west. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south aisle s really the Moreby Chapel of 1336 and as you can see it is a pretty hefty addition. Right: The lovely ladies who were cleaning out the church when I visited kindly dug out the key to the old south door for me. I hope they don’t lose it because I understand that Timpsons are fresh out of blanks. I wish had out something there to give a sense of scale but actually this is a long way from being the biggest church key I have seen. One assumes the lock mechanism is not tenth century! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south doorway and the tower. This is a church surrounded by trees and it is almost impossible to get a “full” shot of it. Right: An alabaster and marble monument in the south aisle dedicated to John Acklam (d1611) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

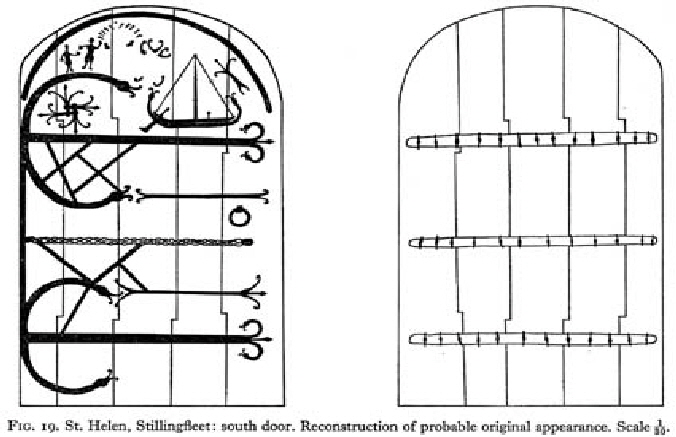

I found this speculative reconstruction of the door on the internet. The longship has a mast and some rigging. Some of the other devices are still difficult to understand, however. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - St Brigid’s Cross |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On the left is one of the pieces of ironwork from Stillingfleet’s ancient south door. Skipwith Church - only five miles from Stillingfleet as the crow flies - also has a magnificent mediaeval door that is decorated wholly with geometric designs. In the centre is a picture of one of those pieces. If you look closely, although the two are different in execution they are very similar in design. There are four arms of a cross but they intersect with each other at the centre. Each arm is terminated by decorative flourishes. In the picture on the right you can see a picture of St Brigid of Kildare holding just such a cross that even today is made by folding rushes. It’s not a good picture but you will see that the rushes are knotted together near the end of each arm leaving a little flourish as in these ironwork designs. If you Google images of St Brigid you will see myriad examples. So what are they doing on these church doors you might ask? Well, putting a St Brigid’s cross on a door is regarded as protection against harm. Coincidentally I saw the TV Historian Janina Ramirez - who specialises in first Millennium history - talking this week about St Brigid being her favourite of the early saints. She explained that Brigid might not even have existed but was probably a development of the Brigid who existed in pagan Irish mythology. I’m not going to talk more about this because there is a lot to see on the internet. There are some interesting implications here. Firstly. Brigid was - and is - primarily an Irish saint but she was evidently “known” in Norman England. The symbolism, however, would hardly have been everyday. The same, of course, is true of the circle interlaced by arcs design on the doorway itself - see above. Skipwith’s door (as opposed to its doorway) is decorated all over with exactly the same motif. So these churches have two esoteric designs in common. We have to be careful not to read too much into this but it seems that they were probably influenced by the same monastery - even the same monk. Secondly we have at these two churches imagery inspired by Plato’s philosophy and by a “saint” who was probably a pagan and not a Christian character. Moreover, however you wrap it up, Brigid’s cross is really a good luck charm. The ecclesiastical equivalent of a horseshoe! All this does give you a good idea of how much of a hotchpotch Christian thought was at that time. That is before we get involved in the interpretation of the voussoirs on the many Norman arches in this area. There are those that feel able to interpret their Christian meanings (Rita Wood’s “Paradise” is a fascinating adventure into that “world”). I don’t have the expertise myself but if you read the work of those that do you will realise how much the imagery owes to mythology and non-Christian culture. Christianity was a kind of cultural Hoover. You don’t think so? Well, just remember whose book the so-called “Old Testament” originally was! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||