|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

It is totally dominated by its original rood screen which is complete with Lincolnshire’s only surviving rood loft which extends all the way to the roof of the church itself. That it survived the Reformation is almost certainly to the church’s remoteness and insignificance. Although it appears very plain, there are plenty of signs of the original paintwork to be seen. Filling most of the rest of the church are a few very old and rustic benches. The font is a plain Norman tub. Really, there is little more to be said about this tiny church. I always feel that the farmyard churches are an antidote to an overdose of ecclesiastical grandeur. See Coates-by-Stow and Stow-in-Lindsay on the same day in order to understand the extraordinary diversity to be found in the English parish church. |

|

||

|

||

|

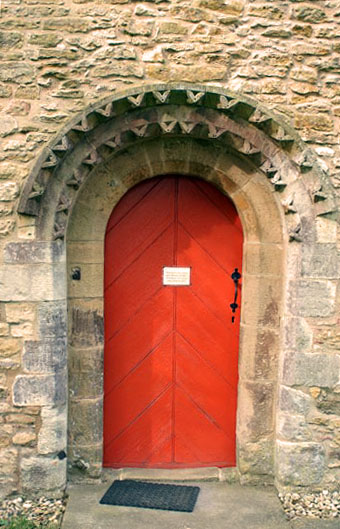

Left: The northern aspect with its rather bizarre of mixture of windows in four different architectural styles. Note the unused and bricked up archway in the west wall, as well as blocked north doorway. Right: The south side with its Transitional period doorway, its door painted a very fetching red! There are a couple of Tudor style windows and a blocked priest’s door. There are no signs of blocked windows so I surmise that the later ones obliterated the earlier ones. |

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

Left: The Transitional south door. The doormat is modern. Centre: Coates has some nice little brass monuments. This one is William Butler (d.1590 aged only 26 years) and his wife, Elizabeth. In the middle is their daughter, Priscilla, wrapped in swaddling. See the larger Butler monument below. Right: Fragments of mediaeval stained glass |

|

|

The rood screen completely dominates the church. In the centre is a recess that would have housed the rood (cross) itself. Note to the left of the screen, partly obscured by the pulpit, an Easter Sepulchre. See the footnote below for more about this. |

|

|

Looking through the screen to the west wall. Not least of the fascinations of this screen is that you can see how wide the platform is. When you see a “screen” where the loft part is missing it is quite difficult to understand how it was actually used. This was a tiny rural church so the physical distance between priest and parishioners was very small. Yet it was still considered important for the priest to be able to conduct some of the rituals from the height of the screen. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The altar as seen from the rood screen. Right: I have to presume that there was once some sort of effigy beneath this canopy but perhaps the congregation could no longer afford the space it would have used? Anyway, we now see it housing these two small brasses. |

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The rood loft with a king post helping to support the trusses. Note the oval mark left of centre. Right: This close-up reveals that the oval mark is actually raised above the surface of the wood and painted. A halo perhaps? |

|

|

|

Two close ups of the supporting structure for the rood loft. I don’t know if they are original but they are certainly rustic! |

|

|

|

Left: There are very clear signs of old painting on the rood loft. Centre: The entrance to the rood stair. In most churches you will see only the top entrance/exit isolated and sticking out like a sore thumb with no stair and no rood screen to serve. Right: An alabaster monument to Brian Cooke (d.1653) |

|

|

|||||

|

Two images of the detail on the screen and we have to presume that some of it is restored or replaced since the original |

||||||

|

|

|||||

|

Left: The simplest of Norman tub fonts betraying a damp problem within the church. The Easter Sepulchre is in the background. Right: The arms of Charles I. For fairly obvious reasons these are not common. Apart from his early demise (!), these arms would not have been terribly fashionable during Cromwell’s Commonwealth! Again we can presumably attribute this to Coates’s isolation. |

|

|

|

Left: The benches and floor are rustic to say the least. This must be a cold old place in the Winter! Right: The west end with the uncompleted tower arch. The royal arms are to the right. |

|

|||||

|

I loved this brass monument so much that I decided to reproduce it in a large size. My Latin is non-existent so I am grateful to Alan Durham who emailed me with this translation (and corrected my earlier misconceptions) : “Charles, first born son of Anthony Butler of Coates by Stow St Mary, squire, married Douglas, third daughter of Marmaduke Tirwhit of Scotter, squire”. The date is 1602. Scotter is fourteen miles north of Coites. There is wonderful detail here even on the images of the eight children. Three of them bear skulls so I surmise that they pre-deceased their parents. Note the wonderful colouring on the coats of arms. |

|||||

|

Footnote 1 - Easter Sepulchres |

|||||

|

I will quote here from G.H.Cook’s classic book, “The English Mediaeval Parish Church (pub.1954). “Of the many rites and observances of the mediaeval church, the ceremony of the easter sepulchre...was universal in parish churches. It was in the nature of a liturgical drama, symbolising the Entombment and the Resurrection of Our Lord. On Good Friday, amid solemn ceremonial, the Blessed Sacrament, placed in a small receptacle, was laid in the Easter Speulchre, a tomb-like structure which was erected to the north of the high altar. Watched day and night, it remained there until the early hours of Easter Sunday when it was transferred to the high altar....Generally, the Easter Sepulchre was a movable piece of furniture consisting of a timber framework...which was draped with hangings or palls and sometimes faced with carved panels depicting the closing scenes in the life of Our Lord, the Burial and the Resurrection.” |

|

Footnote 2 - The “Motley Crew” |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||