|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These rebates are of a size out of all proportion to the windows themselves. The interior, however, is very definitely Norman in style albeit extraordinarily rich and sophisticated. The ambiguity of it all is completed by the Transitional style priest’s door. This is a chancel designed and built by masons with early knowledge of the Gothic revolution gathering pace across the English Channel but without yet having the confidence or the nous to go the whole hog. It is a beguiling structure. The arcade arches are plain but sophisticated, lacking the Norman fetish for zigzag moulding. They too predict the Transitional style to come. We know then that both of the aisles are of Norman origin, Yet this is completely hidden on the outside by Tudor style windows and brick-built battlements and buttresses. The clerestory and south porch are also Tudor. So we come to that bruiser of a west tower. It is as unambiguously Tudor as the east end is Norman. Few parish churches can show such contrast and unusually the two structures are equally fine. When the tower was built the nave was shortened by one bay to the west to accommodate it. One or two bits of the lost Norman tower are incorporated into the Tudor chancel arch. The tower is as sophisticated as it is impressive with large rectangular windows, a tower stair at the south east corner and bold rectangular windows, as well as stone inserts for contrast.. Above all, perhaps, one simply has to admire the aesthetic beauty and the sheer craftsmanship that of this huge acreage of red brick. We in the UK are all mighty familiar with brick building and it would be all too easy to pass swiftly over the gorgeous structure we see here at Castle Hedingham. Both inside and out there is a lot to be seen here. Perhaps the real gem is the fourteenth century chancel screen. It survived mainly because its imagery is secular. There are several carved faces to be see and rather remarkably the Church Guide suggests that they are identifiable with a cast including Edward II, Piers Gaveston his supposed catamite; Edward’s wife Queen Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer who together overthrew and did away with Edward and Gaveston in 1327. Supposedly the screen was commissioned by John de Vere, 7th Earl of Oxford and one of Edward III’s trusted captains in 1357. It is an intriguing idea but I have found no collaboration of this theory and I wonder whether the Earl would have been making this Good vs Evil point thirty years after the event? Jenkins places the date the screen at 1400 and I think he is more likely to be right looking, given the highly developed Perpendicular style of it. There is also a small set of misericords, although only one of these could be called iconic. The black marble tomb of the fifteenth Earl is of great interest. A confidante of Henry VIII, he carried Anne Boleyn’s crown at her coronation. Of course, it is this connection with the de Vere family - the Earls of Oxford - that has defined this church and its development. It was built by the first Earl Aubrey replacing an earlier church of which there is only fragmentary evidence. The village was a pilgrimage site on the route to Bury St Edmunds and there was a healing well as well as a hospital (hotel) for passing pilgrims. Doubtless, the church had some relics of its own. Aubrey was also responsible for the impressive Hedingham Castle - a Norman keep dating from about 1140 - and a priory near the castle gates. The de Vere earldom did not die out until 1703. If you vaguely think you might have heard that “de Vere” name in a different context then see my footnote. |

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west, the scene is dominated by the might Transitional style chancel arch under which the fifteenth century screen stretches proudly. Note the sophisticated - albeit plain - mouldings of the arcade arches and that the pillars alternate between octagonal and round in profile. These are Norman arcades: but Norman arcades which presage an architectural revolution. The two westernmost bays have pointed arches and are fourteenth century insertions. At the far end the rare and precious Norman wheel window stares proudly down. Right: The chancel. The scale is grand, the alternating niches and window rebates sophisticated. Note, however, the pointed windows within those round-headed spaces. Note also the trio of small lancet windows, surely another foretaste of the Early English style of twenty when triple lancets would become an iconic design albeit with taller windows. There was Victorian restoration work here but I think we can be satisfied that the space is largely unchanged from the original. |

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

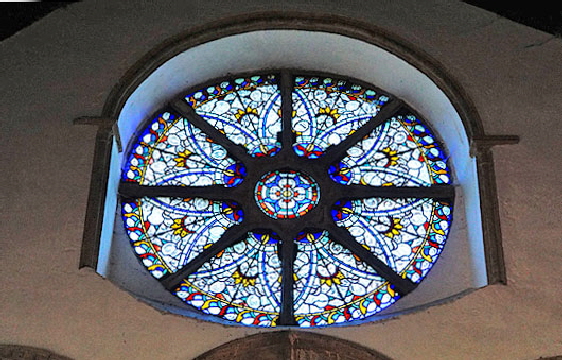

Left: The south side of the chancel with its Norman arcading and under-sized windows. Right: The wheel window from the inside. The glass is Victorian. |

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: This is a part of the chancel that we can safely assert to be a total re-imagining by the Victorian architect Henry Woodyer. It is Norman in style but very obviously faux. What did it replace? I suspect that this is a total remodelling. The triple sedilia for priest, deacon and sub deacon if it existed before would have been a later Gothic affair. To the left of the sedilia, covered by the cloth, is the piscina. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The view to the west. The tower arch is mighty - and Tudor, leading to the Tudor west tower beyond. Right: One of the Norman capitals. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

The central section of the chancel screen. It is very sophisticated both in design and execution. Too much so, in my opinion, for the 1357 date mooted by the Church Guide.. Like most Gothic screens it is skeumorphic - a wonderfully pretentious word for which there is sadly no know synonym - which is to say that it imitates the structural architecture of the day. 1357 would be a very early date for such an advanced Perpendicular design and was, moreover, a time when the country was still in post-Plague shock. It is not impossible that the wealth and influential de Veres were able to engage a carpenter able to carry out such avant-garde work but I can’t help thinking that this date is speculative and intended to reinforce the notion that the carved heads (you can see these at the ends of some of the bosses) can be associated with Edward II - see my introductory paragraphs. It is a beguiling story but I believe that the screen dates between 1370-87. To find out why see my description of the misericords below. Oddly, the guide produced for children says 1400. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chancel Screen Boss Imagery: Left: In the Church Guide’s account I have to assume they see this as Isabella of Hainault. The long-lived crespinette, in which her hair bound either side of her head (and also known as “templers”) is of no use in dating her unfortunately. She is not shown with a crown even though she was Queen to King Edward II The mother of Edward III, and for some time his regent, it is a debatable point whether she would have been represented without a crown. Second Left:: the most entertaining of the bosses seemingly of an animal with a dragon around its neck. Second Left: Unidentifiable head. Right: Is this figure wearing a crown? Is this who the Church Guide takes to be Edward II? I believe it to be Richard II - see below. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The nineteenth century is an oddity but not unpleasant in its own way. There is clearly a nod to mediaeval Gothic but the decoration seems entirely freelance. Centre: A much older oddity. It is a holy water stoup, of course, and one day it probably was sited outside the church. Its decorative design - a cat with radiating stems - is upside down so this is very obviously not the original use of this stone. The Church Guide suggests it was originally the base of a wayside cross. Right: The lid of the de Vere tomb - see below. |

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The holy water stoup now - via the magic of Photoshop - the right way up. Right: The de Vere tomb. This was of the fifteenth ear, John (1482-1540) l and his second wife, Elizabeth Trussell. John had a distinguished career as a confidant of Henry VIII. Unsurprisingly his record under the Henry is one of toadying devotion to all of his King’s whims. He helped pursue Wolsey, carried Ann Boleyn’s crown at her coronation, and was a judge in the trial of Lord Montagu and the Marquess of Exeter. He embraced Henry’s religious reforms. Thus did he stay in favour and become a Knight of the Garter and was Lord Great Chamberlain from 1526 until his death. He attended the Field of the Cloth of Gold. You were either with Henry or agin him and John prospered as one of Henry’s inner circle. The tomb is of “black marble” which is not marble at all. His four daughters are visible here but the sons are hidden between the monument and the wall. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: De Vere and his wife occupy the bottom part of the tomb slab. John wears armour. This was no mere affectation. He was knighted by Henry after the Battle of the Spurs at Tournai in 1513 and I do wonder if it is Tournai Marble from which this monument is constructed? he is bare-headed and kneeling in prayer, a gauntlet visible by his knees. Note the Tudor rose. Right: The Earl of Oxford coat of arms occupies the top part of the slab. The central design is of the Order of the Garter with its “Honi Soit Qui Mal y Pense” wording. Atop the helm is a boar, one of the personal symbols of the de Veres which we will see again outside the church. The supporting figures are curious. On the left appears to be an angel (note the wings) with the body of a fish. To the right is a stag. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

I don’t know why there are misericords at Castle Hedingham. As far as I know this has not been a monastic or collegiate church. Monks would have observed the eight different pre-Reformation masses each day and needed to rest their weary, arthritis-ridden bodies. Although services would have been held every day in a parish church it was impracticable to observe all of the monastic offices separately. Matins, lauds and prime would have been combined together in the early morning, followed by a combination of Terce, Sext and Nones either side of morning mass. Vespers and Compline would have been combined in the evening, This is a schedule that would make the modern parish priest blanch but it seems that it was not so taxing as to require misericords for the clergy in most parish churches. In his splendid book “Going to Church in Medieval England” (Yale, 2021) Nicholas Orme discusses the gradual intrusion of more wealthy members of the congregation into he chancel during services. One wonders, them whether these misericords were for the benefit of the de Veres family? This is somewhat supported by the fact that all of the misericords except this one are restrained and with a number of appearances of shields and crowned heads? In short, these look like aristocratic misericords. The one above, however, is the exception and it gratifyingly follows the satirical tradition of such furniture. A fox, recognisable by his long luxuriant tail, drags away a monk hung upside down from a pole. His cassock is hanging from his waist. I am not sure what the allegory is here. Foxes epitomised mischief in mediaeval minds, not least in the Reynard the Fox fable. Priests were frequently lampooned and were not, it seems, always respected as upstanding moral examples. I am sure, without knowing what exactly lies behind this imagery, that it is no complimentary to the clergy! On the left supporter a wolf leads the way tootling on a shawm. To the right is a green man figure. Or a lion. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Four more misericords - there are six in all. Top Left we have the ubiquitous Pelican in her Piety. The crowned head bottom right is interesting. Who is it? You will note he is moustachioed but not bearded. This rules out the heavily bearded Edward III and the similarly hirsute Edward II who would be an unlikely candidate anyway. Henry V was clean-shaven. Richard II was, in his contemporary portraits, moustachioed and very lightly bearded. I am pretty convinced this is the man we are seeing here. Why? Robert de Vere, the ninth earl, was one of Richard’s closest friends. He was made Duke of Dublin and Marquess of Ireland. So close was he to Richard that one historian suspected a homosexual relationship. He was hugely unpopular with his peers and the strength of his influence was a factor in Richard’s overthrow by Henry Bolingbroke. De Vere led Richard’s troops to defeat at the Battle of Radcot Bridge (in Oxfordshire) in 1387. He escaped but was attainted and died in a boar hunt in Louvain, France in 1392. Sir Aubrey de Vere succeeded as tenth earl and the de Vere lands restored. If you look carefully at the chancel screen roof boss above, you will see that the moustaches are identical. I believe we are seeing the work of the same carpenter and this dates the screen to around 1370-1387. Richard II himself regained power in 1389 but was deposed in 1399. It is just possible that Aubrey commissioned these carvings, but John seems much the more likely. This would make the other crowned figure Richard’s wife Anne of Bohemia who died in 1394. Henry IV, by the way, was also bearded. You may call me Sherlock! |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This is a pretty thing and being modern does not change that! This lovely carving commemorates Musette Majendie who died in 1981 (the Church Guide mistakenly says 1991), She owned Hedingham Castle. In the 1930s she hosted a number of “camps” at the castle (seen in the background to the monument) to re-train unemployed young Scouts and the camps were run on Scouting principles. She was a quite remarkable woman and perhaps more worthy of commemoration here than most of the grander folk! Centre: The church is justly proud of having no less than three original Norman doors This one in the south doorway is called the “Skin Door” because traces of human skin were found under the nails in the nineteenth century. Local tradition has it that some unfortunately who stole from the church was nailed to it for punishment. In mediaeval times, however, the punishment for stealing from a church was flaying alive, a dreadful death so perhaps some of the skin was fixed here as a warning? If you run your eye along the horizontal strap of the upper hinge you will see a metal protrusion that is, it is said, either a basilisk or a de Vere family boar. Right: Detail of the upper hinge. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The nave has a fairly rare double hammerbeam roof. Right: I like these models people produce of their churches. The work people put in is amazing and short of sending up a drone (and don’t think I haven’t thought of that!) there is no better way to visualise a church in its entirety. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

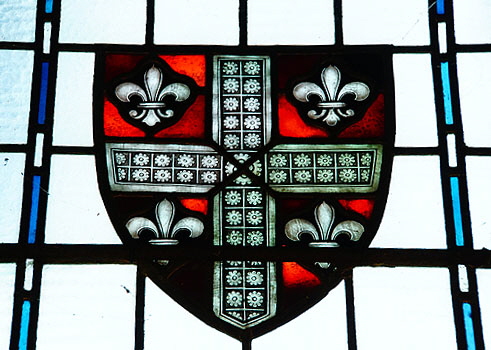

These two panes of stained glass are in the south porch which is unusual by and standards. It took quite a lot of digging to find out whose these arms belonged to. They belong to the Ashurst family. When the de Vere line died out the castle at Castle Hedingham was bought by Sir William Ashurst, a distinguished banker, merchant and politician, in 1713 . He died in 1720, leaving his estate to his great granddaughter Lady Margaret Lindsay who was married to Lewis Majendie. Musette Majendie’s scouting memorial is shown above. The Lindsay descendants still own the castle. The glass in the porch, therefore, seems capable of dating to that very short period of 1713-1720 between Ashurst’s acquisition of the castle (and associations, of course, with the parish church) and his death in 1720. The arms on the right are the Ashurst arms. Those on the left incorporate then in two of its quarters but the pictorial imagery (a serpent and a dove?) is something of a mystery. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

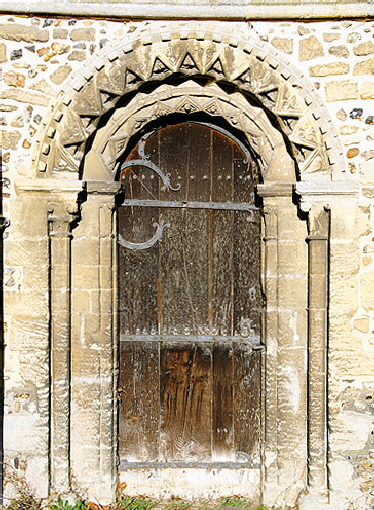

Left: Demonstrating that churches can be hard to photograph in bright as well as low light this is the east end of the north aisle. The arch to the right is later. What is interesting here is the fourteenth century doorway from the rood loft, now marooned. This must show an approximate position for an earlier rood screen that that which we see today and which is to the right of the right hand bay here. Yet the chancel arch is unequivocally twelfth century! Nobody seems keen to explain this anomaly. Pevsner did not even notice it. Or maybe he preferred to omit what he could not explain? I have seen suggestions that he chancel arch was modified in the fourteenth century but it seems inconceivable that it was actually moved further east. Another church, another mystery <sigh>. Centre: The south doorway cunningly its beautiful Norman wooden door (see above) behind these modern green monstrosities, The doorway itself is, again in a very late Norman or Transitional style. Right: The priest’s door on the south side of the chancel also shows its late twelfth century stylistic schizophrenia. This is a beautiful composition and the door itself is, again, original Norman with a particularly gorgeous upper hinge. Note the way the ironwork curls sinuously over the top of the door in the same fashion as on the south door (above) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: I spy another twelfth century doorway, this time on the north side of the nave. Characteristically the less-loved north side has a slightly less elaborate doorway than its southern counterpart and you would have to call its design austere. It has, however, yet another original twelfth century door! Centre: This chancel east window perhaps shows the strongest early Gothic as opposed to late Norman characteristics. It is pointed, has a hood mould to divert water from the glass itself and has little colonettes. Yet above it is a very Norman wheel window and its imposts connect to a characteristic Norman string course. Right: The west end of the Tudor brick-built west tower. It has a magnificence all of its own. |

|

|

|

Left: This course of designs is found above the west side of the tower, above the rectangular west window. The imagery is all of the de Vere family. The Church Guide (an excellent if expensive one - £5 at the time of writing in 2022) helpfully interprets most of them. See below. Right: Surely one of the noblest examples of brickwork in England? The tower from the south east. Unusually, the clerestory and aisle battlemented parapets are also of brick. Someone with more knowledge of art and aesthetics than myself might be able to explain why rectangular windows look just fine on a brick structure but usually look dreadful on a stone building? |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A mariner’s whistle represents the post of Lord High Admiral held by the thirteenth earl, It is not at all obvious because of weathering but the longitudinal raised bit at the bottom is the actual whistle/ At the top is a looped lanyard that continues to the whistle via a central toggle. Interestingly, you can see how the mason has cut out little vertical and horizontal guidelines to help with his geometry. Centre: The five-pointed star emblem of the de Vere family. It was carried by Aubrey de Vere at the First Crusade. Right: The wild boar, another de Vere family emblem. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Perhaps the most fascinating and also one of the most weathered images. It is a “jack” for winding a crossbow string. On the right you can just about make out the winder. Invisible around the outside is the Garter motto “Honi Soit Qui Mal y Pense”. The jack was a play upon words for the thirteenth earl, John or Jack de Vere (1442-1513). This particular earl was a military man from the top of his helm to the tips of his sabatons. He was a leading light in the Lancastrian cause during the Wars of the Roses. He suffered many vicissitudes as the wars ebbed and flowed between the two great houses and somehow managed to navigate through imprisonment and loss of his lands before being one of Henry Tudor’s commanders at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Indeed he commanded the archers and employed an arrow-shaped formation that is known to history as the “Oxford Wedge”. He was one of Henry VII’s closest confidants and also enjoyed high favour with Henry VIII before his own death at Castle Hedingham. You might have thought, as I did, that the longbow and not the crossbow would have been the main type of projectile weapon at Bosworth and you would be right. But the Henry Tudor Society (we have a society for everything in England!) says that a very powerful version of the crossbow called an “Arbalest” was used for the last time at the battle. Centre: An ox in a ford! It seems the Oxfords signed themselves as “Oxinford” in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Thus we have two examples here of imagery that are plays upon the name of an illustrious family, Whatever our image of the mediaeval aristocrats they did not flinch from a little fun their own expense. Right: The Chair of Estate for the Lord Great Chamberlain. The de Veres held this post from the twelfth century until 1625, a remarkable fact. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: Above the clerestory windows are alternate star and boar images of the de Vere family. Note the brickwork surrounding the windows. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south porch of the early sixteenth century. Centre: The east end. The three lancet windows predict the most iconic feature of Early English architecture that was to sweep England in the next decade or two but the string courses are Norman. Above is the wheel window. Right: The churchyard cross is the war memorial of 1921. That tricked this writer who did not that the shaft was Norman, although he did, to be fair to himself, realise that the base was Anglo-Saxon! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The wheel window. As far as I know, the only others are at Peterborough Cathedral and at the parish churches of Patrixbourne and Barfreston in Kent. This example is later than either of those two galleries of Norman sculptural exuberance. This is The Last of the Wheel Windows, in fact. It differs from the other two in not having monster carvings at the outside of its spokes. It is more restrained and sophisticated but a real treasure. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the north east. This too is not an unattractive vista. Right: On the east end of the south aisle the mason has left us this whimsical and very common late mediaeval carving. Because he could. Ok? |

|

Footnote: The 17th Earl and “William Shakespeare” |

|

I well remember sitting a Public Library in Birmingham in about 1963 when a friend announced to me that his teacher had said that Sir Francis Bacon had written the plays attributed to Shakespeare. Well, what did I know? I regurgitated that tripe for a good couple of years until I was finally introduced to some of the texts themselves. I did not tell my fierce, black-gown clad English Lit teacher that he was mistaken about the authorship. I don’t know in how many countries the notion that Shakespeare was not written by Shakespeare has any sort of currency. In England Christopher Marlowe is seen as another contender it seems. The theory, you see, is that William Shakespeare was a commoner who could not possible have had the “education”. The principal “I know something you don’t” contender to be the “real” Shakespeare nowadays is none other then the seventeenth Earl of Oxford, one Edward de Vere (1550-1604). Guess what? There is a de Vere Society. I quote from its website: “The de Vere Society is dedicated to an appreciation and celebration of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1550-1604) as the true genius behind the literary pseudonym €˜William Shakespeare”. Note the certainty of that statement. I told you we English have a society for everything! Nearly sixty years on from my public library experience, I was earnestly informed by a dear (and very intelligent) friend over dinner that she had that week seen a film “Anonymous” by Ralph Emmerich and it had convinced here that de Vere certainly was Shakespeare. The son of a Stratford-upon-Avon glover maker, she informed me, could not have been educated enough to have written his plays. The film, by the way, seemed to have lived down to its title. Well as a Warwickshire man born and bred you would not expect me to have any truck with this hogwash and you would be right. It is a crying shame that the principal argument against poor old Will seems to boil down to the insinuation that he was an ignorant member of the lumpen proletariat (he attended Stratford-upon-Avon Grammar School whose war cry in my days of competing against them in cross-country running and rugby” was “Come on Shakespeare School”). How ready we British are to imbue our aristocratic forebears with great intellect in total contradiction to their record of grasping mediocrity. It’s funny, isn’t it? I never hear this codswallop about Marlow who was the son of a Canterbury bootmaker! That is because he is not a poppy tall enough to be worth cutting down, presumably. To put a contrary view, one website I visited said: “Shakespeare, as the son of a leading Stratford citizen, almost certainly attended Stratford's grammar school. Like all such schools, its curriculum consisted of an intense emphasis on the Latin classics, including memorization, writing, and acting classic Latin plays. Shakespeare most likely attended until about age 15” . That doesn’t sound to me like an ignoramus. How about you? You will have your own views. Mine simply is that Shakespeare is Shakespeare until someone proves otherwise. Perhaps in due course someone will come up with a killer argument that Shakespeare was a pseudonym. In the meantime I for one put these notions in the drawer alongside “Covid-19 is a lie”, ”Trump won the Election” and “A group of Paedophiles rule the world”. Mate, you’ve got to prove it not just keep saying it to your fellow believers. Forty years ago (sorry, more reminiscences) I remember starting to read the then wildly popular book “Chariot of the Gods” by Erik von Daniken. It postulated the notion that earth had been visited by aliens God knows how long ago. These kindly chaps had given our ancients the know-how to build pyramids and stuff. You will note that this plays to the recurring theme of “how could these stupid people have done something so impressive”. Where did they get the education? I well remember that a few pages in von Daniken made the point that perhaps there was life on other planets that did not require water, oxygen and so on but used different substances. I thought that was a fair point and, to tell the truth, I think it still is! Are we being too narrow in out thoughts? Then von Daniken goes on to say that to him the mysterious lines at Nazca in Peru look very like a network of modern runways and that they could, therefore, be somewhere that the aliens landed. You see the balminess of it all? First he accuses scientists of being bound by conventional science and then say that the “aliens” may have needed a landing ground very like our own. I stopped reading at that point. These are the sorts of knots contrarians habitually tie themselves up in. Oh, by the way? Did you know that Sir Isaac Newton (educated The King’s School, Grantham) was really the seventy-third Earl of Lundy Island? I’m setting up a society to promote this indisputable fact. Remember where you heard it first. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

Heathrow of the Gods. Nazca Plain, Peru |

|||