|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

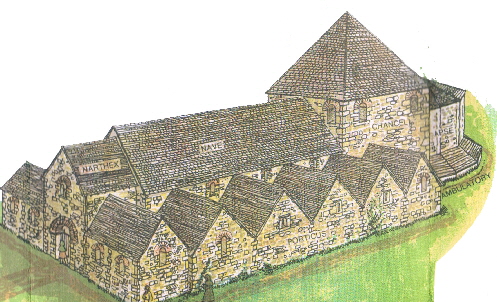

would not have looked much like the monasticism of the Cistercians, the Cluniacs and the like, although some of the monks may have observed the Rule of St Benedict. Others may well have been “secular” clergy who did not observe the Rule. Such men would not have been isolated within a closed community: on the contrary they would have been administering to the spiritual needs of a wide community as a beacon of Christianity within the area. As well as being a rare Anglo-Saxon minster survival, Brixworth is one of only three (the others being Great Paxton and Lydd) surviving English churches built according to the so-called “Basilican” plan that had its origins in Rome. So very way you look at it, Brixworth Church is one of the oldest and most important buildings of any kind in England. Not all you see, however is from that original church, and some of that original church has disappeared. The most obvious casualty was a whole raft of porticuses - or side chapels - on both sides of the existing nave. There would have been five on the south side alone and each of the large filled-in archways in the picture above would have been an entrance to a porticus from the nave. In itself, this proliferation of altars proclaims the veneration of saints, as we would expect in a minster church. Above those arches we see tall clerestory arches. These too are original. Then again, the western tower below the string course is also of that original church. But it was not then a tower: it would have been the central portion of a narthex or western porch area and, again, a very rare survivor of the original basilican plan. That surviving central portion of the narthex, however, would have been flanked by two other sections, thus embracing the whole width of the churches, porticuses and all. Within, the church now has three cells. The nave is the original one. The chancel area originally supported a low squat tower. Beyond it was an apse - again, a classic feature of the basilican plan. That has been subsequently rebuilt. See the picture below reproduced from the Church Guide |

|

|

|

of it now survives. Then it was remodelled completely as a rectangular space in the fifteenth century but was restored to something approaching its original form in 1865. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

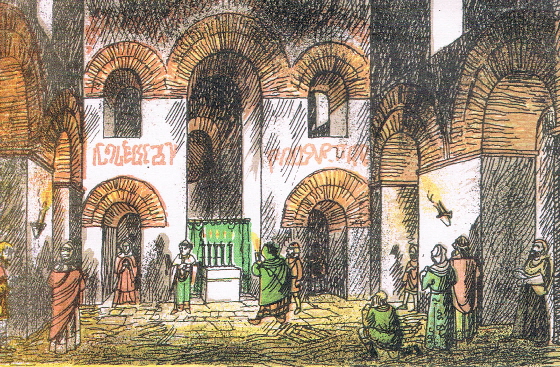

The view to the east end of the church. To left and right you can see the entrances to some of the original porticuses. You can see that the round arches are made from two courses of mortared stone tiles, a very idiosyncratic feature of this church. The arch in the foreground denotes the start of the original chancel that rose above nave and porticuses to form a low tower. Originally there was a triple archway; a tall central arch flanked by two lesser ones. Above these lesser ones were two more openings, The chancel arch we see now is fourteenth century but it springs from those original upper arches. At the east end we see an Anglo-Saxon arch to the apse with two flanking windows to the outside. The east window itself is not original. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The west wall of the church is one of the most famous sights in English church architecture. We see the original doorway to the narthex, now the west tower. Above that is another doorway of barely smaller proportions. It probably led to a long-disappeared wooden west gallery from which relics were perhaps sometimes shown to the pilgrims and worshippers below. Intruding into the arch is a triple window arrangement. This dates from Norman, not pre-Conquest, times. Porticus and clerestory arches are very clear to left and right. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The sanctuary arch. Note the other arches - one gothic - but in particular at ground level on either side the entrances to the ambulatory outside the apse. Right: The triple Norman window on the west wall. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north east corner of the apse. The north window is the only original Anglo-Saxon window surviving of the apse. The low wall protects the unwary from tumbling into the ambulatory below! Centre: The south east corner of the apse. You could just discern the blocked arch of its doorway. Right: The Anglo-Saxon bell turret. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This little Saxon door nestles on the south side of the tower. It was not originally an external doorway at all but led to the now-demolished south cell of the original narthex. Note the Saxon “herringbone” masonry course above it and the tower stair turret to the left. Note also the tiles recycled from Roman buildings. Right: This blocked doorway on the north side of the apse led down to the ambulatory. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This is the “Brixworth Eagle of St John”. Taken from a Saxon cross-shaft, it rests by the south door protected by a perspex sheet. Centre: The tower stair turret from the west. The limit of the original Saxon work in the base of the tower is clearly marked by the string course. Right: The stair turret is eleventh century, a little later than the tower itself. The herringbone visible here in courses right up to the flagpole indicate that it is Saxon rather than Norman. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north wall. The north side showing three clerestory windows and four porticus arches. The porticuses would have had gabled roofs, joined together to form a kind of saw tooth configuration. The original clerestory windows were smaller and would have peeped out in the spaces between the “teeth”. The ones we see today are larger and date from the the removal of the porticuses in AD 970. The gothic windows to the chancel are perhaps the most jarring bit of “modernisation” at this church, closely followed by the awful battlementing of the nave. Although the need for parapets to disguise the roofline (especially if it was once lead) is understandable. plain ones would have served the church better on this occasion. Right: The blocked archway from the central part of the narthex to the demolished north part. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the north east. Not the polygonal apse. Right: Copied from the Church Guide, an artist’s impression of the interior of the church showing the original configuration of the chancel arch with two flanking arches and two window spaces from which the present chancel arch springs. It perhaps helps us to imagine the dark and atmospheric interior of the original church. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote: Councils of Clovesho |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the eighth and ninth centuries there were seven councils held at a location recorded as Clovesho or Clofeshoch between AD742 and AD825. They were attended by kings of Mercia, nobles and bishops and have sometimes been seen as something akin to England’s first parliament which you might feel is pushing it a bit! Nobody knows where it was located and it has been called “the most famous lost place in Anglo-Saxon England". I am not so sure about that, as some very famous and important battle sites of the first millennium are also lost to us. Nevertheless, Clofeshoch is indeed a mystery, although it is known to have been within the Kingdom of Mercia. Three or four locations have been suggested but the most plausible is reckoned to be Brixworth although I do not know why. Quite a lot is known about who attended these and what was discussed. They were in the nature of synods and related to important matters of religion but it is fascinating to see Church and State reaching decisions together. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||